“Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.” Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote these words over a century ago. It typified the Progressive Era’s focus on “good government” and civil administration. Since the first “publicity” law in 1910, political spending transparency has been an unchallenged campaign finance virtue. Scholars, policymakers, and courts have given so-called “disclosure” near universal praise as a corruption preventive.

But a draft research paper by Michael D. Gilbert of the University of Virginia School of Law casts doubt on prevailing wisdom. Combining law and economics and infusing storylines from a popular TV drama, Gilbert takes a contrarian view. It’s not that disclosure has no positive benefits, but that it’s not an unalloyed good. It comes with tradeoffs and even can facilitate the corruption it seeks to stop. As Gilbert states, “Monitoring [government officials] deters corruption just as patrol cars deter speeding. But sunlight does something else too. It lowers the transaction costs of corrupt bargaining.”

Gilbert shows disclosure’s double-edged sword through hypotheticals, real examples, and popular culture. In the crime drama ‘The Wire,’ transparency laws both prevent and aid corrupt bargains. Detectives use campaign finance records to connect drug dealers and corrupt officials. But the mayor uses the same records as a cudgel against “riding the middle” donors who hedge their bets by supporting both candidates in an election.

The negative aspects of disclosure arise from the information gain to bad actors. Gilbert breaks down corrupt bargains in economic terms as lowering three specific costs: search costs, negotiation costs, and enforcement costs.

Gilbert gives a hypothetical of corruptible Senator X and dirty CEO Y to show how disclosure lowers costs in all three phases.

Using only private information, search costs are high for CEO Y looking for a corrupt senator. If he picks wrong, he risks jail. He doesn’t know what price range Senator X will sell her vote, setting up even more danger. And uncertainty about verification and payment raises costs even more.

Government-mandated transparency changes the calculus. The corrupt CEO has a much easier go finding a corrupt senator predisposed to his cause because he can view prior donations.

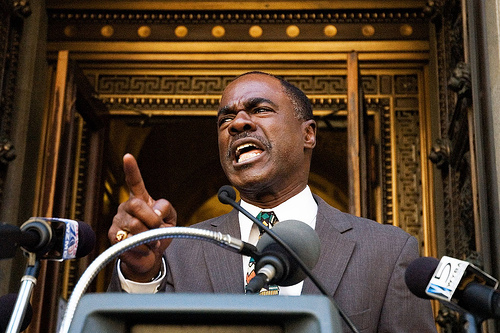

Conversely, public records allow politicians like Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) to essentially extort contributions based on a contributor’s public record.

On the negotiating front, disclosure allows both the corruptible senator and the CEO to size each other up in terms of voting records and contribution history. Former House Majority Whip Tom Delay kept a record of favorable and unfavorable contributors that he showed lobbyists requesting favors. This “crude menu” was only possible because of searchable records.

Finally, disclosure allows each party to easily track enforcement. The senator can view payments to a super PAC supporting her, and the CEO can watch the vote on C-SPAN.

“In sum,” Gilbert explains, “disclosure records lower all of the transaction costs of corrupt bargaining. This facilitates exactly those quid pro quos that disclosure aims to prevent.”

Gilbert does not argue all transparency is bad; only that it comes with tradeoffs. “It exposes contradictions in received wisdom. Why, for example, do many election law scholars accept the secret ballot while expressing unbridled support for campaign finance disclosure? The purest scholarship seeks truth, and finding truth requires resistance to dogma and group think.”

Policymakers and judges share this academic blind spot with deleterious effects on government efficiency. Group think has stifled contrarian views on campaign finance disclosure and perhaps other transparency initiatives Gilbert cites, like open government meetings, FOIA, even sex-offender registries and mugshots of arrestees.

Clearly, conventional wisdom on disclosure needs re-thinking. Those making, interpreting, and commenting on our transparency laws must take a more balanced approach that has been missing this past century. Michael Gilbert’s essay is an important first step.