In response to growing concern over political corruption, Congress amended the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (“FECA”) in 1974 to, among other things, set a dollar limit on how much money individuals could contribute to a federal candidate’s campaign at $1,000 per election.[1] This new “contribution limit” was challenged as violative of the First Amendment in Buckley v. Valeo.[2] There, the United States Supreme Court upheld FECA’s $1,000 limit because no evidence was presented to suggest the statute would have any dramatic adverse effect on campaign funding.[3] Still, the Court acknowledged that contribution limits could have a severe impact on political dialogue, if the limits prevent candidates from amassing the resources necessary for effective advocacy.[4]

In Buckley, the Court held FECA’s contribution limit to “exacting scrutiny.” Since Buckley, many, including Justice Thomas, have voiced dissatisfaction with this standard, preferring the more stringent test of “strict scrutiny” to align with the Court’s other First Amendment jurisprudence.[5] Nonetheless, subsequent contribution limits remain subject to exacting scrutiny. The standard is substantial and requires statutes to be rid of several “danger signs” while ensuring that challengers can mount effective campaigns against incumbent officeholders.[6]

In the ensuing decades since the amendments to FECA and the Court’s ruling in Buckley, a new and creative way to restrict speech has arrived in the form of industry-based contribution bans.[7] These bans typically target an industry and prohibit players in that industry – and sometimes their employees – from contributing to candidates. This means that, by virtue of their profession or who they work for, some individuals are banned from contributing any amount to candidates, and sometimes even political action committees and party committees. The Supreme Court has not yet weighed in on the constitutionality of this type of limit.

Selectively restricting some Americans’ ability to engage in political debate is a ploy one might expect from a corrupt, totalitarian regime, not a free democracy. State and federal laws prohibiting political contributions from certain individuals in certain regulated industries pose both constitutional and policy concerns that should not be overlooked. This paper surveys those issues.

I. Not all industries are treated equally.

When legislators choose to prohibit the ability to make political contributions, proponents argue that the restriction is necessary to eliminate improper influence and safeguard against corruption. But often, the prohibition only applies to some industry players. Not only does this mean that some stakeholders are treated unequally, but the citizenry is disadvantaged too. In a republic where citizens rely on their elected representatives to implement policy, it is essential for voters to be informed. A prohibition on the amount of money an industry or its employees can spend during a campaign necessarily quells the opinion of some while elevating others – often without the general public knowing that a key stakeholder was restricted. Consider the following real-world examples:

-

-

- Federal law prohibits individuals who enter into a contract, or who are bidding on a contract, with any agency or department of the United States government from contributing to federal campaigns, which includes all House, Senate, Presidential, and Vice-Presidential candidates.[8] Under this law, all such corporations and individuals contracting with the government are treated as the same prohibited industry. This law purports to prevent corruption involving contractors, who admittedly have transparent interests in a core function of the federal government. Interestingly though, no prohibition applies to contracting officers – those who review, grant, and maintain government contract bids and execution on behalf of their agency or department.[9] Likewise, no prohibition applies to the judges who adjudicate government contract claim disputes.[10]

-

-

-

- In 2019, the Los Angeles City Council voted to prohibit campaign contributions from real estate developers with projects needing city approval.[11] But consider that nearly every proposed project has an opponent. Landlords might not want competition from new office or residential developments. Local residents often oppose new developments, a phenomenon known as “not in my backyard.” Surely, this was an effort to combat improper contract awards, but there are a lot of players on the field, and only one group of them loses a vital right to support candidates. The Council previously enshrined in the city’s code a commitment to purchasing goods and services from manufacturers and distributors whose practices “improve public health and safety, reduce pollution, [and] conserve natural resources . . . .”[12] Yet environmentally friendly manufacturers and distributors, who similarly rely on securing the Council’s approval and purchases for financial prosperity, are subject to no such political contribution ban.

-

-

-

- More recently, a coalition of current and former district attorneys have called upon the American Bar Association and the California State Bar to pass an ethics rule prohibiting law enforcement agencies and police unions from endorsing or donating to candidates in prosecutor races.[13] Proponents of the rule point to professional entanglements law enforcement officers may have with prosecutors as proof that campaign contributions from one to another may unduly influence a prosecutor’s decision making.[14] Interestingly, no similar calls have been made to prohibit endorsements or contributions to candidates for district attorney from similarly entangled, high-priced defense and civil attorneys, or groups advocating for criminal justice reform.[15]

-

As we can see, some industries have been deemed too potentially corrupting while others, with the same degree of stake, have not. The solution to this selectivity is not to implement bans on those not yet covered, but rather, to eliminate industry-based bans entirely.

II. Lower courts need Supreme Court guidance for reviewing industry-based contribution bans.

The United States Supreme Court has recognized “that contribution limits might sometimes work more harm to protected First Amendment interests than their anticorruption objectives could justify.”[16] Here, we consider a measure even more drastic than limits: outright bans on political contributions merely based on the fact that an individual is engaged with an industry that some elected officials deem worthy of such a prohibition.

The Supreme Court has established that political contributions to candidates fall squarely within the First Amendment’s protection of speech and association.[17] Accordingly, when political contributions are regulated to further the governmental interest of deterring quid pro quo corruption or its appearance, the government bears the burden of proving a regulation’s constitutionality.[18]

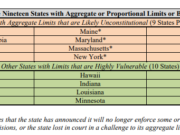

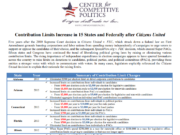

Without Supreme Court guidance, differing standards of review have emerged from lower courts tasked with reviewing industry-based contribution limits. Take two recent examples:

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

-

-

- As discussed previously, 52 U.S.C. § 30119 prohibits federal government contractors from contributing to any political party, committee, or candidate. No consideration is made for what type of government contract captures a federal contractor (e.g., energy, construction, academia) or what percentage of the contractor’s income is comprised of government contracts; instead, all federal contractors are treated as a homogenous industry. Three plaintiffs, two contractors for the U.S. Agency for International Development and one law professor, contracted to prepare a report about science and regulation. These individuals wanted to make campaign contributions during the 2012 federal elections but were barred by § 30119.[19] Together, they sued the Federal Election Commission, alleging that the statute violated their rights under both the First Amendment and the Equal Protection component of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.[20] Unfortunately, many of the plaintiffs’ claims became moot before the court could rule.

-

Still, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the prohibition in § 30119, finding it closely drawn enough to address the contracting context, which has a “very specific quo for which the contribution may serve as the quid: the grant or retention of the contract,” because the statute applies to contractors.[21] The court made no distinction between seemingly more entangled, powerful corporate contractors and sole proprietors with small contracts like the plaintiff law professor, who was temporarily retained to prepare an informational science report. Indeed, the court admitted that “less direct evidence is required when, as here, the government acts to prevent offenses that ‘are successful precisely because they are difficult to detect.’”[22]

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

-

-

- Section 1513 of the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development and Gaming Act imposed “political contribution restrictions on an array of people and entities with financial interests in gaming industry operations.”[23] This array included “affiliates, intermediaries, subsidiaries, and holding companies” of those possessing gaming licenses.[24] Like the constitutional claims in Wagner, two gaming license holders challenged the statute, alleging First Amendment and Equal Protection violations. In response, Pennsylvania cited similar bans in Louisiana and New Jersey, in combination with “human nature,” which may result in corruption.[25] The Third Circuit, however, was not so persuaded by the “common sense” logic that proved successful in Wagner.[26] In the absence of evidence supporting “fit” nor an explanation as to why an overwhelming majority of states (with similarly robust gambling industries) need not resort to an outright ban like Pennsylvania, the Third Circuit determined that the Commonwealth failed to meet its burden to prove that § 1513 was a closely drawn, proportional response.[27]

-

As illustrated by the above cases, two statutes with the same purported purpose (anti-corruption) and same result (industry ban) received disparate judicial scrutiny. While the D.C. Circuit approached its review of § 30119 through a government reform lens, the Third Circuit approached its review of § 1513 through a traditional contribution limit lens that encompassed free speech and association inquiries.

III. It is unlikely that the Supreme Court would uphold an industry-based contribution ban.

While the Supreme Court has considered state and federal contribution limits, it has yet to consider industry-based contribution bans. In the event of a challenge, it is unlikely that any such ban would pass constitutional muster under the Court’s past decisions in this area.

Like the $1,000 contribution limit upheld in Buckley, industry-based contribution ban proponents may point out that such bans leave industries and their employees free to engage in independent expenditures or volunteering if they are so inclined to participate politically.[28] However, when subsequently reviewing aggregate contribution limits, Justice Thomas’ concurrence in McCutcheon v. FEC pointed out that the Court’s post-Buckley First Amendment decisions rejected “proxy speech” approaches.[29] Indeed, contributions have a uniquely expressive value, as they allow contributors to specify both which candidates they support and the intensity of their support.[30] While other forms of political participation, like independent expenditures, are meaningful, they are not the same as direct campaign contributions.

Especially when a contribution limit is zero dollars, as it is for industry-based contribution bans, the ability for affected individuals to engage in other political activity should not be considered a cure for the outright First Amendment deprivation perpetrated in the first place. Not to mention, some industry-based contribution bans apply to gifts made to political action committees and political parties, as well as to candidates.[31]

In the same vein, the Supreme Court has placed a premium on the ability of challengers to mount effective campaigns against incumbent officeholders for the sake of democratic accountability.[32] The Court noted in Randall v. Sorrell that contribution limits that are too low will inhibit effective challenges. Here, we consider a limit that is not just lower than all of the contribution limits ever reviewed by the Supreme Court; we consider statutes that restrict an entire group of people, no matter their influence on industry decision making, based on their employment within the field.

For example, the industry-based contribution ban on federal contractors applies not only to large, government contracting firms as corporate entities, but also to individuals in their personal capacities, such as Professor Wendy Wagner, who was retained by the government to prepare a scientific report.[33] No consideration is made for federal contractors even when the percentage of their business that relates to the government is of seemingly de minimis value.[34] Likewise, New Jersey’s casino industry-based contribution ban applies not only to the casinos themselves as corporate entities nor only to casino owners, but also to “key employees” of New Jersey casinos in their personal capacities.[35] According to statute, a manager of casino security guards is considered a “key employee”; consequently, these managers are prohibited from making political contributions to candidates and state parties while off duty despite performing nearly identical tasks and carrying the same low degree of industry influence as other security managers in New Jersey not subject to the industry ban.[36]

The above highlighted cases also shed light on another departure from First Amendment jurisprudence. Unlike how the government must present evidence of “real harm” to restrict commercial speech,[37] the government has no such hurdle when unilaterally choosing a certain industry and entirely restricting that industry’s ability to engage in political speech via contributions. The very ability to arbitrarily identify a targeted industry makes this sort of contribution prohibition significantly more dangerous and abusable than blanket contribution limits upheld in the past.

A major red flag is raised when one’s First Amendment protections differ depending on their line of work. No such variety can be found in the Court’s religious exercise or freedom of the press jurisprudence.

IV. Industry-based contribution bans signal bad policy.

When political contribution bans are placed only on certain players, the game is no longer fair. Imagine challenging an opponent to a tennis match; though, because he is in the business of manufacturing the rubber often found on tennis racket grips, the league prohibits him from spending any money on a tennis racket. Sure, the opponent is free to find other means to compete with you – he could spend money on fancy tennis shoes or dig out an old wood racket from his garage. On the other hand, you may be related to the referee, but nonetheless, no tennis racket prohibition applies to you. Does this seem like a fair match?

Individuals tied to any industry are just as much deserving of political representation and fairness to compete in the political arena as those who are not, particularly when affected industries are selected by the very elected officials tasked with setting the policies that regulate that industry. In response to recent calls for a ban on political contributions from law enforcement agencies and police unions to prosecutor races, the President of the San Francisco Police Officers Association (“SFPOA”) pointed out that “California’s most ardent criminal apologists want to ban unions and . . . rank and file police officers . . . from informing our communities about candidates who have a direct impact on their safety.”[38]

Industry-based political contribution bans chill political participation by some members of our society who could otherwise better inform the electorate if it were not for their association with an industry deemed dangerous or unsympathetic by elected officials. In any democracy, there is a natural and intentional cord of sympathy between representative and constituent, as candidates are dependent on the suffrage and inclinations of their fellow citizens.[39] Ingratiation should not trigger the assumption of corruption.[40]

Finally, we must ask ourselves what it means if, in order to trust our elected representatives, we must legally ban some individuals from monetarily supporting their campaigns? The SFPOA President addressed this question: “[i]f any attorney running for office does not have the moral and ethical principles to separate politics from their sworn duty, they should turn in their Bar card and not seek public office.”[41]

After all, political contributions are publicly disclosed and accessible for any interested party to review. Voters, challengers, and regulators can decide for themselves if any candidate has acted in a way that indicates corruption once in office. When political contribution lists can be retrieved in a matter of seconds online, loosely asserted corruption fears can be aired and examined without also needing to place contribution bans on entire industries and their employees.

Conclusion

Without needing to present evidence of localized or particularized corruption, local, state, and federal lawmakers have found a new and creative way to restrict the speech of those they find harmful through industry-based contribution bans. Currently, industries are disparately affected in varying jurisdictions while lower courts give disparate treatment when determining the constitutionality of such restrictions. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that any such ban would pass constitutional muster based on the Supreme Court’s past decisions regarding political contributions. Considering the myriad of bad policy that industry-based contribution bans signal to the electorate, in addition to constitutional concerns, Supreme Court clarification would be welcome in this important area.

[1] See Joseph E. Sandler, “Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971,” The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Retrieved on August 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1078/federal-election-campaign-act-of-1971 (discussing amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 to limit political contributions). See generally James Bopp, Jr., All Contribution Limits Are Not Created Equal: New Hope in the Political Speech Wars, 49 Catholic U. L. Rev. 11, 15 (1999) (overviewing the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971’s pretext).

[2] 424 U.S. 1 (1976).

[3] Id. at 21.

[4] Id.

[5] See Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230, 267 (2006) (Thomas, J., concurring) (“Accordingly, I would overrule Buckley and subject both the contribution and expenditure restrictions of Act 64 to strict scrutiny, which they would fail.”); Brief of the Cato Institute and the Institute for Justice as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, Thompson v. Hebdon, 140 S. Ct. 348 (2019) (No. 19-122) (“Campaign Contribution Limits Warrant Heightened Judicial Scrutiny”). Available at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/19/19-122/113625/20190826140043349_19-122%20Amicus%20Brief–PDFA.pdf.

[6] See Randall at 249; see also Thompson v. Hebdon, 140 S. Ct. 348 (2019) (per curiam) (confirming Randall’s precedence value when reviewing contribution limits).

[7] See Phila. Fire Fighters’ Union Local 22, AFL-CIO v. City of Philadelphia, 286 F. Supp. 2d 476, 478 (E. D. Pa. 2003) (describing Philadelphia’s ban on political contributions by uniformed fire fighters); State ex rel. Gerstein v. Hialeah Race Course, Inc., 245 So. 2d 53, 55 (Fla. 1971) (describing Florida’s ban on political contributions to political parties and candidates by any person holding a horse or dog racing permit); see generally Caleb P. Burns and Eric Wang, “Regulated Industry Contribution Bans at Issue in Illinois Fight Over Marijuana Money,” Wiley Rein LLP. Retrieved on August 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.wiley.law/newsletter-May_2017_ELN-Regulated_Industry_Contribution_Bans_at_Issue_in_Illinois_Fight_Over_Marijuana_Money (May 2017) (listing states that impose contribution restrictions on certain regulated industries).

[8] 52 U.S.C. § 30119; 11 C.F.R. § 115.1; see also 11 C.F.R. § 113.1(c) (defining “federal officeholder[s]” as the President or Vice President of the United States or a Senator or Representative serving in Congress).

[9] See The Hatch Act, 5 U.S.C. § 7324(b)(1) (listing political activity deemed permissible for government employees).

[10] Compare id. (indicating the lack of any legal ban on government contract judges, such as the Civilian Board of Contract Appeals judges, making political contributions), with Code of Conduct for United States Judges, Canon 5(A)(3) (indicating an ethical instruction to all judges to refrain from making political contributions).

[11] L.A., Cal. Code § 49.7.37 (2020); see Editorial Board, “L.A. says it banned developer political contributions. But the job is only half-finished,” The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on August 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-05/ban-developer-contributions-behested-payments (December 5, 2019).

[12] L.A., Cal. Code § 10.31(b)(4) (2009).

[13] Maria Dinzeo, “DAs Demand Ban on Endorsements and Donations to Prosecutors by Police,” Courthouse News. Retrieved on August 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.courthousenews.com/das-demand-ban-on-political-donations-endorsements-by-police-to-prosecutors/ (June 1, 2020).

[14] See id.

[15] Id.

[16] Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230, 247 (2006) (citing Nixon v. Shrink Mo. Gov’t PAC, 528 U.S. 377, 395-97 (2000)).

[17] FEC v. Colo. Republican Fed. Campaign Comm., 533 U.S. 431, 440 (2001).

[18] Deon v. Barasch, No. 18-3325, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 17092, at *9 (3rd Cir. June 11, 2020) (citing McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. 185, 210 (2014)).

[19] Wagner v. FEC, 793 F.3d 1, 3 (2015).

[20] Id. The Institute for Free Speech, then known as the Center for Competitive Politics, filed an amicus curiae brief with the Cato Institute supporting the challengers. Available at: https://www.ifs.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Amicus-Brief-of-Cato-Institute-and-Center-for-Competitive-Politics.pdf (July 10, 2013).

[21] Id. at 53, 84.

[22] Id. at 47.

[23] Barasch, No. 18-3325 at *6; see 4 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 1101 et seq. (2010).

[24] William J. Palatucci and Steven H. Sholk, “Third Circuit Finds Restrictions on Political Activity Violate Exacting Scrutiny Standard of Review,” New Jersey Law Journal. Retrieved on August 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.law.com/njlawjournal/2020/06/24/third-circuit-finds-restrictions-on-political-activity-violate-exacting-scrutiny-standard-of-review/ (June 24, 2020).

[25] Barasch, No. 18-3325 at *16.

[26] Id. at *18.

[27] See id. at *18, *19.

[28] See Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 28 (1976) (upholding FECA’s $1,000 contribution limit, as it leaves “persons free to engage in independent political expression, to associate actively through volunteering their services . . . .”).

[29] McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. 185, 229 (2014) (Thomas, J., concurring) (citing FEC v. Nat’l Conservative Political Action Comm., 470 U.S. 480, 495 (1985) and Nixon v. Shrink Mo. Gov. PAC, 528 U.S. 377, 413, 414 (2000) (Thomas, J., concurring)).

[30] See Craig Engle et al., Buckley Over Time: A New Problem with Old Contribution Limits, 24 J. Legis. 207, 218 (1998) (characterizing contributions as opposed to votes).

[31] See “Regulated Industry Contribution Bans at Issue in Illinois Fight Over Marijuana Money,” supra note 7 (“Louisiana prohibits contributions to state candidates and PACs supporting or opposing candidates from entities involved in the gaming industry and from certain affiliated individuals.”); N.J. Stat. Ann. § 5:12-138 (prohibiting contributions to any committee of any political party from certain casino industry individuals).

[32] See Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230, 248, 249 (2006) (“That is because contribution limits that are too low can also harm the electoral process by preventing challengers from mounting effective campaigns against incumbent officeholders, thereby reducing democratic accountability.”).

[33] See Wagner v. FEC, 793 F.3d 1, 3 (2015).

[34] See Factual and Legal Analysis, In re: Suffolk Construction Company, Inc. (MUR) 7099, p. 4 (FEC, May 31, 2017) (finding the respondent in violation of § 30119, even though federal contracts constituted less than 0.5% of all its contracts serviced in the past five years and less than 0.7% of its total revenue during that five-year period).

[35] N.J. Stat. Ann. § 5:12-138.

[36] N.J. Stat. Ann. § 19:41A-5.1.

[37] See Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Serv. Comm’n, 447 U.S. 557, 581 (1980).

[38] Dinzeo, supra note 13.

[39] See The Federalist Papers No. 35 (Alexander Hamilton).

[40] Id.; see also McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. 185, 208 (2014) (“Spending large sums of money in connection with elections, but not in connection with an effort to control the exercise of an officeholder’s official duties, does not give rise to such quid pro quo corruption. Nor does the possibility that an individual who spends large sums may garner ‘influence over or access to’ elected officials or political parties.”); Bradley A. Smith, Unfree Speech: The Folly of Campaign Finance Reform, 96 (2003) (“Our political culture does not consider a contribution for campaign use to be particularly corrupt, and millions of American citizens make campaign contributions and never feel the least tainted by the process.”).

[41] Dinzeo, supra note 13.