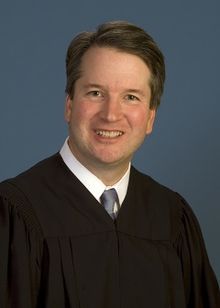

Hon. Brett Kavanaugh

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (2006-Present)

This post is the first in a series exploring the free speech rulings of Judge Brett Kavanaugh, a federal appeals court judge reportedly being considered for Justice Kennedy’s seat on the Supreme Court. (Part II is here, part III is here, and part IV is here.) We begin our analysis with five significant campaign finance opinions he authored or joined.

Judge Kavanaugh has seen his fair share of campaign finance and political speech cases. That’s for good reason. The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where he has served since 2006, has jurisdiction over most challenges to federal campaign finance laws and regulations. We analyze the following such cases in this post.

- EMILY’s List v. Federal Election Comm’n, 581 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2009)

- SpeechNow.org v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010) (en banc)

- Independence Institute v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 816 F.3d 113 (D.C. Cir. 2016)

- Pursuing America’s Greatness v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 831 F.3d 500 (D.C. Cir. 2016)

- Wagner v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 793 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (en banc)

Judge Kavanaugh ruled in favor of free speech in four of these cases. The exception was Wagner, where he joined an 11-0 opinion siding with the Federal Election Commission. His opinion in EMILY’s List is particularly impressive. Foreshadowing later rulings in Citizens United and SpeechNow, Judge Kavanaugh clearly articulated a First Amendment right for associations to spend money in support of candidates. The opinion demonstrates an ability to anticipate trends in First Amendment jurisprudence before they fully take hold.

In the other three cases, Judge Kavanaugh applied careful scrutiny to government regulations that impeded free political speech. He authored the opinion in Independence Institute, which ordered that a special three-judge district court review the Institute’s challenge to McCain-Feingold’s donor disclosure requirements, and joined rulings striking down FEC regulations in SpeechNow and Pursuing America’s Greatness.

EMILY’s List v. Fed. Election Comm’n

Citizens United and SpeechNow.org imposed a sea change in the law regarding how political committees could be structured and funded. But even before the creation of super PACs, nonprofit organizations strained against the regulatory burdens placed on them by Federal Election Commission (“FEC”) rules and regulations.

EMILY’s List v. Federal Election Commission dealt with a spate of regulations that the FEC put in place against certain nonprofit corporations in the aftermath of the 2004 presidential election. Specifically, in response to the so-called “527” expenditures made during the 2004 election against President Bush and Senator Kerry, the FEC imposed a panoply of limits designed to treat nonprofit corporations, functionally, as if they were political parties.

In an opinion that preceded and foreshadowed the Citizens United and SpeechNow.org opinions, Judge Kavanaugh wrote an opinion for the Court reversing the lower court and striking down these regulations on First Amendment grounds. The Court decided that nonprofits such as EMILY’s List, a pro-choice, partisan nonprofit dedicated to electing pro-choice Democratic female candidates for office, ought to have “the right to spend unlimited money to support their preferred candidates” and “receive full First Amendment protection.” 581 F.3d at 8-9. “A non-profit that makes expenditures to support federal candidates,” Judge Kavanaugh wrote, “does not suddenly forfeit its First Amendment rights when it decides also to make direct contributions to candidates.” Instead, so long as it complied with modest regulation, it was “entitled” to make certain “advertisements, get-out-the-vote efforts, and voter registration drives” out of an “account…not subject to source and amount limits.” Id. at 12.

Judge Kavanaugh’s opinion noted that “it might seem incongruous to permit non-profits to receive and spend large…donations when political parties and candidates cannot,” but the Constitution provides a clear mechanism to “eliminat[e] this perceived asymmetry” namely “to raise or eliminate limits on contributions to parties or candidates.” Id. at 19.

SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission

(Current Institute for Free Speech President David Keating and Ed Crane, now a member of the IFS Board, were plaintiffs, and IFS attorneys were among counsel for Plaintiffs in this case.)

Federal law regulates as a political committee any organization with the primary purpose of advocating the election or defeat of federal candidates. Political committees may contribute money to candidates or make “independent expenditures” – spending on speech that calls for the election or defeat of a candidate, but is not coordinated with any candidate or political party.

This case asked whether an organization that makes only independent expenditures may receive contributions in excess of the limits imposed on political committees. SpeechNow was an unincorporated group that wanted to make expenditures advocating for the election of federal candidates that support free speech rights. SpeechNow’s lawsuit asserted that limits on contributions to independent expenditure-only organizations violated the First Amendment.

Judge Kavanaugh joined the unanimous decision by Judge Sentelle. The court ruled that the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling had resolved the question.

From the opinion:

“In accordance with that decision, we hold that the contribution limits of 2 U.S.C. § 441a(a)(1)(C) and 441a(a)(3) are unconstitutional as applied to individuals’ contributions to SpeechNow… because Citizens United holds that independent expenditures do not corrupt or give the appearance of corruption as a matter of law, then the government can have no anti-corruption interest in limiting contributions to independent expenditure-only organizations.”

In addition, the D.C. Circuit ruled that independent expenditure-only organizations could be required to comply with reporting and disclosure requirements imposed on political committees, as opposed to those imposed on organizations making independent expenditures. However, SpeechNow had stipulated that it would disclose all contributors if it had been permitted to file reports as an organization making independent expenditures. The opinion did not take note of this distinction. Again, from the opinion:

“We cannot hold that the organizational and reporting requirements are unconstitutional. If SpeechNow were not a political committee, it would not have to report contributions made exclusively for administrative expenses. See 2 U.S.C. § 434(c)(2)(C) (requiring only the reporting of contributions “made for the purpose of furthering an independent expenditure”). But the public has an interest in knowing who is speaking about a candidate and who is funding that speech, no matter whether the contributions were made towards administrative expenses or independent expenditures. Further, requiring disclosure of such information deters and helps expose violations of other campaign finance restrictions, such as those barring contributions from foreign corporations or individuals. These are sufficiently important governmental interests to justify requiring SpeechNow to organize and report to the FEC as a political committee.”

Independence Institute v. Federal Election Commission

(The Institute for Free Speech represented the Independence Institute in this case.)

The Colorado-based Independence Institute wanted to run a radio advertisement in support of a bill in Congress that would reform federal sentencing laws. The ad asked citizens to communicate their support for the bill to Colorado’s U.S. Senators at the time, Mark Udall and Michael Bennet. Because the ad would run near the 2014 election, in which Udall was a candidate, the ad qualified as an “electioneering communication” subject to federal regulation under the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act.

Federal law requires organizations that make electioneering communications to report their spending on the ad and the names and addresses of donors who gave $1,000 or more “for the purpose of furthering” the ad. The Independence Institute filed a lawsuit arguing that BCRA’s disclosure requirements are only constitutionally valid for communications that are “unambiguously campaign-related.” As provided by statute, the Institute sought a three-judge court to review its case. The district court denied its request, ruling that the issue had been foreclosed by previous challenges to BCRA’s disclosure regime in McConnell and Citizens United. The Institute appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Institute argued that two features distinguished its case from Citizens United. First, the Institute’s speech was purely focused on a legislative issue, whereas Citizens United’s speech was express advocacy or its functional equivalent. Second, the Institute was a 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit whereas Citizens United was a 501(c)(4) advocacy group.

Writing for a 2-1 majority, Judge Kavanaugh reversed the district court and granted the Institute’s request for a three-judge court. The majority ruled that the difference in tax status was sufficient to entitle the Institute to a three-court judge. However, it did not address the Institute’s primary argument that BCRA’s disclosure requirements are only valid for communications that are “unambiguously campaign-related.”

From the opinion:

In Citizens United, the Supreme Court did not address whether a speaker’s tax status or the nature of the nonprofit organization affects the constitutional analysis of BCRA’s disclosure requirement. See 558 U.S. at 369. And the FEC cites no precedent from the Supreme Court (or any other court) rejecting the argument advanced here by Independence Institute. The nature of our system of legal precedent is that later cases often distinguish prior cases based on sometimes slight differences. See, e.g., Arizona Christian School Tuition Org. v. Winn, 563 U.S. 125 (2011); Michigan v. Bryant, 562 U.S. 344 (2011); see generally Richard M. Re, Narrowing Precedent in the Supreme Court, 114 COLUM. L. REV. 1861 (2014). Here, we cannot say that Independence Institute’s attempt to advance its as-applied First Amendment challenge is “essentially fictitious, wholly insubstantial, obviously frivolous, and obviously without merit.” Shapiro, 136 S. Ct. at 456, slip op. at 7. That is not to suggest that Independence Institute’s argument is a winner. Independence Institute’s 501(c)(3) argument may or may not prevail on the merits, but Section 2284 “entitles” the Institute to make its case “before a three-judge district court.” Id.

Independence Institute also contends that the First Amendment bars compelled disclosure of donors unless the electioneering communication is unambiguously campaign-related. The FEC responds that McConnell and Citizens United squarely rejected that argument. Cf. Republican National Committee v. FEC, 130 S. Ct. 3544 (2010), affirming Republican National Committee v. FEC, 698 F. Supp. 2d 150, 156-58 (D.D.C. 2010) (rejecting this distinction of McConnell and Citizens United). We do not address that argument. Because Independence Institute has advanced at least one argument – the 501(c)(3) argument – that is not “essentially fictitious, wholly insubstantial, obviously frivolous, and obviously without merit,” the case must proceed to a three-judge court. Shapiro, 136 S. Ct. at 456, slip op. at 7. When a case falls within Section 2284 and requires a three-judge district court, “a single judge shall not . . . enter judgment on the merits” of any claim. 28 U.S.C. § 2284(b)(3); see Shapiro, 136 S. Ct. at 455, slip op. at 5.

Pursuing America’s Greatness v. Fed. Election Comm’n

Judge Kavanaugh also recently sat on a three-judge panel that struck down an FEC regulation. This case challenged the FEC ban on PACs “using candidates’ names in the titles of their websites and social media pages.” 831 F.3d at 503. The opinion striking down this ban was written for the Court, including Judge Kavanaugh, by Judge Griffith.

Federal law prohibits committees that are not authorized by a candidate from “includ[ing] any candidate’s name in its own name. Id. at 503-504. Thus, a committee not formally authorized by the Mike Huckabee presidential campaign could not call itself Mike Huckabee for President.

Pursuing America’s Greatness (“PAG”) did not challenge this provision directly. Instead, it targeted a regulation that banned the use of a candidate name in a committee’s projects unless the project was “clearly and unambiguously” opposed to the candidate being named. PAG did not oppose Mike Huckabee, but rather wanted to run “a website and a Facebook page named ‘I Like Mike Huckabee,’ which PAG worried would run afoul of the FEC’s naming rules.” Id. at 504. Going forward, PAG intended to create similar online presences concerning other federal candidates, should it be allowed to do so.

The FEC attempted to argue that the ban on using a candidate’s name was not a speech ban, but rather a “disclosure rule[].” Id. at 507. As the Court noted, under Supreme Court precedent, “[w]e view disclosure rules far less skeptically than we do bans on speech.” Id. at 507.

But the Court determined this was not a disclosure rule, which would “require the speaker to provide more information to the audience than he otherwise would.” Rather, it “prevents PAG from conveying information to the public.” Id. (citations and quotation marks omitted, punctuation altered for clarity).

Applying Justice Thomas’s recent majority opinion for the Supreme Court in Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 135 S. Ct. 2218 (2015), the D.C. Circuit then applied strict scrutiny to the FEC’s speech ban. This meant that the FEC had to show its regulation was the least restrictive means of furthering a compelling governmental interest. The FEC proffered an interest in fighting “voter confusion,” which the Court declined to determine was, in fact, a compelling interest. Id. at 510. Rather, the Court noted that there were less restrictive means of furthering an interest against voter confusion, such as an actual disclosure requirement stating that PAG was not, in fact, Mike Huckabee’s authorized committee.

Accordingly, the Court voted to enjoin the regulation.

Wagner v. Fed. Election Comm’n

In this case, however, Judge Kavanaugh sided, disappointingly, with the Federal Election Commission, and upheld a flat prohibition on the right of “individuals…[to make] federal campaign contributions while they negotiate or perform federal contracts.” 793 F.3d at 3.

Because of a quirk of federal statute, this case was heard by the en banc D.C. Circuit in the first instance. The entire Court voted 11-0 in favor of the FEC in this case, with an opinion written for the Court by Chief Judge Merrick Garland.

The plaintiffs raised two challenges to the ban: a First Amendment objection and a challenge based on the Fifth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

The Court’s opinion rejected the First Amendment challenge by turning to a “historical review,” which it found determined that “the two Court-approved justifications for limitations on campaign activities—to protect against quid pro quo corruption and its appearance, and to protect merit-based public administration—were the justifications that lay behind the contractor contribution statute. Likewise, our national experience supports Congress’ fear that political contributions by government contractors can corrupt and interfere with merit-based administration.” 793 F.3d at 20.

The opinion unfortunately failed to apply real scrutiny to the ban as applied to the only plaintiff before the Court of Appeals. As noted in the Plaintiff’s brief, “[a]fter he retired, he continued to work for [USAID] in an employee status as a reemployed annuitant-consultant.” While he was technically a contractor, “for all practical purposes [he was a] federal employee[].” Notably, federal employees are not banned from making such contributions.

The Court then turned to determine whether the statute was “closely drawn” to these interests, applying a standard first enunciated by the Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo. The Court conceded the ban was “a significant restriction.” Id. at 22.

However, “the contracting context greatly sharpens the risk of corruption and its appearance… in the case of contracting there is a very specific quo for which the contribution may serve as the quid: the grant or retention of the contract.” Id. Moreover, in light of the historical review the Court conducted it found this was “not just a question of risk, but of reality.” Id. Worse: “the appearance problem is also greater: a contribution made while negotiating or performing a contract looks like a quid pro quo, whether or not it truly is.” Id.

Additionally, “because a contractor’s need for government contracts is generally more focused than a member of the general public’s need for other official acts, his or her susceptibility to coercion is concomitantly greater.” Id. at 23. Thus, “the contracting context also greatly sharpens the risk of interference with merit-based public administration.” Id. at 23.

The Court rejected a number of other arguments regarding whether the statute could be more “closely drawn,” noting that while “[w]e do not discount the possibility that Congress could have narrowed its aim even further…the First Amendment does not confine a State to addressing evils in their most acute form.” Id. at 26 (citation and quotation marks omitted).

The Court then turned to an unusual First Amendment claim called “underinclusiveness”: that because the law did not also ban the speech of other persons, such as those that are associated with a firm which also has government contracts or PACs run by a contracting firm, federal employees, or those seeking government benefits, the individual-contractor ban should also fall. The Court “bluntly” rejected this claim, noting that “[t]he First Amendment does not require the government to curtail as much speech as may conceivably serve its goals.” Id. at 27 (citation and quotation marks omitted).

Then, the Court turned to the plaintiffs’ Fifth Amendment claim, which argued that “[e]qual protection is violated…because the statute subjects individual contractors like themselves to a ban that it does not apply to two categories of similarly situated persons: (1) entities and individuals associated with firms that have government contracts (i.e., PACs of contracting corporations; officers, employees, and shareholders of contracting corporations; and individuals who control contracting LLCs); and (2) individuals who are regular employees rather than contractors.”

The Court determined this was “the same argument” as the underinclusiveness argument, pled under the Fifth Amendment as a means to evade the Buckley “closely drawn” standard. Id. at 32. (Fifth Amendment equal protection claims are typically reviewed under the most taxing form of review, “strict scrutiny.”) The Court “reject[ed] this doctrinal gambit.” Id.