Aside from voting, one of the most effective ways Americans can generate change in their government is to speak out and educate more of their fellow citizens on current issues and candidates. Donations to campaigns, parties, and political committees are a powerful way to accomplish this goal. Contributions buy billboards, television spots, Facebook ads, pamphlets, and countless other forms of speech. Salaries for campaign staff, polling, gas for transportation across the country, all manner of campaign buttons, signs, t-shirts, and bumper stickers, and pizza for hard-working volunteers are also paid for with donations from supporters. In short, contributions facilitate the spread of ideas and allow candidates and committees to reach more voters with their message.

Imagine there are two individuals, both of whom are passionate about politics and wish to voice their support for a candidate or political issue. One has the financial resources and job flexibility to take leave from paid work, while the other, who is just as passionate, cannot take time away from work and family obligations to volunteer for a candidate or cause. Rather than contributing his time, the second individual decides he can contribute a portion of his earnings to help a U.S. Senate campaign pay for the same activities the volunteer is helping with. Under current law, the first individual can contribute as many hours as he can muster, creating tremendous value for the campaign. The second individual can only contribute $2,700, simply because the full-time worker’s preferred means of activism is through donations. Both are choosing to forgo money they could spend elsewhere to contribute to a campaign they are passionate about. However, if the volunteer would have made just $10/hour working for the campaign, he would likely exceed the contribution limit in less than two months. So why should the ability of one individual to give be greater than the other?

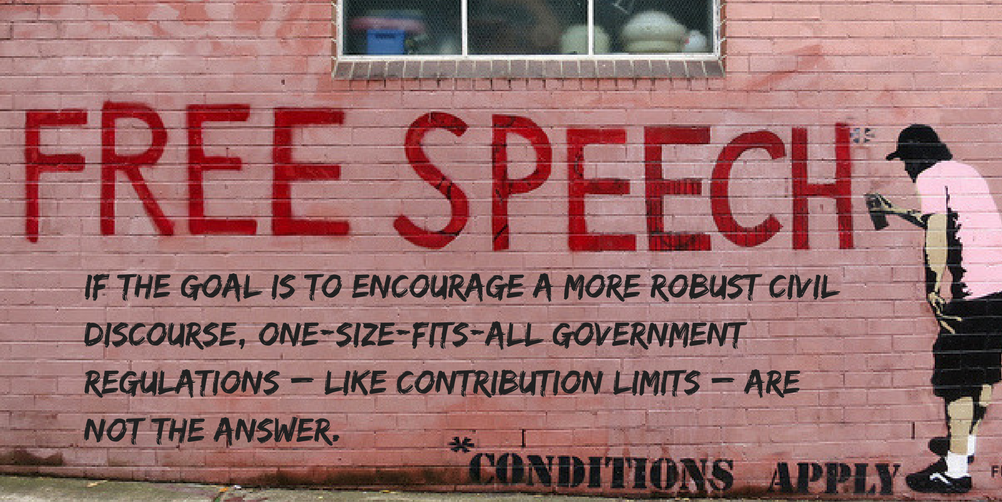

Contribution limits, in effect, are little more than a cap on free speech and free association.

The Court has also been very clear that the only justification for restricting First Amendment speech rights is the prevention of quid pro quo corruption or its appearance, and the burden must always fall on the government to prove any attempts at regulation are narrowly tailored to that end.

Over the years, the Court has struck down some limits. In Randall v. Sorrell, the court struck down limits for being too low. In McCutcheon v. FEC, the Court struck down aggregate contribution limits on the overall amount an individual could give as unconstitutional. And in Citizens United v. FEC (and subsequently SpeechNow.org v. FEC) the Supreme Court and D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, respectively, said limits on independent groups were unconstitutional. In each of those four cases, the court in question ruled that the limits harmed First Amendment activity without showing any anti-corruption interest.

Supporters of contribution limits argue these restrictions diminish corruption and help promote “good” government. However, the data simply do not support those theories. According to the Institute for Free Speech’s analyses of state contribution limits, seven of the seventeen states with low levels of corruption have no or very high limits on contributions to legislative candidates, compared to just four states with low limits on such giving. Additionally, no relationship has been found between a state’s limits on what an individual can give to state legislative candidates and the quality of government in that state. According to rankings of state governance by U.S. News & World Report, the top-four states who are the “best governed” (and eight of the top twelve) have high contribution limits or no limit at all, while four of the five “worst governed” states have moderate or low limits.

Another common argument for speech restrictions in the form of contribution limits is an egalitarian defense. Proponents argue contribution limits prevent some voices from being “drowned out” by the perceived influence of wealthy donors. However, in practice, these limits actually hurt the ability of some groups to support candidates, in favor of others with influence gained through wealth, celebrity, or their occupations.

One of the many problems with regulating speech in an attempt to coerce egalitarian outcomes is that the government simply cannot control it all. The voices of journalists who write for The New York Times and late-night talk show hosts are “louder” than those of other Americans because of their national, sometimes global, platform. But that doesn’t mean we can (or should) restrict the printing of newspapers or what can be said on television to balance things out. The egalitarian solution cannot be more restrictions; it must be more speech to answer the ideas and opinions with which individuals disagree.

The same can be said for campaign contributions. While some will have a greater ability to give than others, restricting citizens’ ability to speak by donating to candidates and causes in an attempt to “level the playing field” only prioritizes speech by some over others. Granting powerful politicians the authority to pick and choose exactly what speech should be favored (or disfavored) is a dangerous path to tread down.

Finally, adherents of stringent limits on campaign contributions argue these restrictions promote a more open and competitive democracy. This rhetoric couldn’t be further from the truth. Running for elected office is incredibly expensive – even more so for candidates running against established incumbents. Paired with the laundry list of benefits enjoyed by incumbent candidates (name recognition, legitimacy in voters’ eyes from their experience, legislative accomplishments to tout, media access, familiarity with would-be donors, and franking privileges for voter outreach, to name just a few), it can be very difficult to topple an incumbent. Limits on what individuals can give to candidates and causes only make it harder for challengers to mount competitive campaigns. For this reason, contribution limits tend to benefit incumbents and preserve the status quo.

Recognizing the failures of contribution limits as a policy and their detrimental effect on free speech and association, lawmakers across the country have increasingly taken action to raise or eliminate various limits. Between 2010 and early 2015, 15 states and Congress had increased or eliminated limits on political giving in some fashion. In 2013 alone, nine states raised or removed their limits. Arkansas and Wisconsin increased their contribution limits in 2015, and, just this year, Kentucky legislators voted to do the same. When advocating for legislation that would increase political giving freedoms, lawmakers consistently explained the harmful effects limits had on their ability to communicate with voters and run effective campaigns.

The failure of campaign contribution limits to achieve their lofty, anti-corruption, egalitarian, and democratic goals stems from their advocates’ fundamental misunderstanding of the essence of the First Amendment. The words “Congress shall make no law…” do not create a positive right for every member of society to be heard that the government must uphold. Rather, they cement the negative right of all citizens to be unrestricted by government interference in their ability to speak and associate freely. If the goal is to encourage a more robust civil discourse, one-size-fits-all government regulations – like contribution limits – are not the answer. Allowing Americans to engage with and speak about issues they are passionate about, in a way that works for them, is a much better solution.