State Aggregate Limits and Proportional Bans under McCutcheon

Likely Unconstitutional or Highly Vulnerable

By Matt Nese

Please note: This report has been updated to reflect state responses to the Supreme Court’s McCutcheon decision.

On April 2, 2014, the Supreme Court issued its decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, which invalidated the federal aggregate limit on contributions by individuals to candidate campaigns and political committees as unconstitutional under the First Amendment. This report examines the aggregate limit and aggregate-like limit statutes in 19 states and D.C., discusses state responses to the Court’s ruling, and examines the constitutionality of these statutes in the wake of the McCutcheon decision.

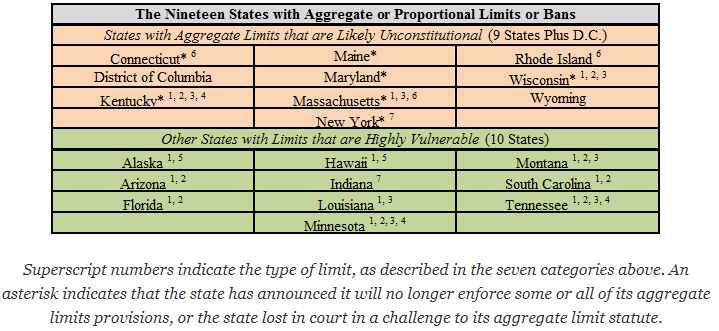

Nine states – Connecticut, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and Wyoming – and the District of Columbia impose aggregate limits in some form on the overall amount entities may contribute to candidates and causes. These limits appear to be unconstitutional, according to the precedent set in McCutcheon.

Another ten states – Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, South Carolina, and Tennessee – impose other forms of limits that operate in a similar fashion to an aggregate limit, leaving them highly vulnerable to a legal challenge, according to the reasoning in the McCutcheon decision. In an illustration of the overwhelming complexity of campaign finance laws, these other limits fall into seven categories: (1) “First Come, First Served” Limits; (2) Aggregate Limits on Recipient Candidates (Party Version); (3) Aggregate Limits on Recipient Candidates (PAC Version); (4) Proportional Bans; (5) Non-Resident Aggregate Limits on Candidates, Parties, or PACs; (6) Aggregate Limits on PAC Donations; and (7) Aggregate Limits on Corporate or Union Donations.

Because of the Supreme Court’s ruling in McCutcheon, the aggregate limit statutes in nine states and D.C., in particular, appear to be unconstitutional. As of July 8, 2014, Connecticut, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York’s election law enforcement agencies have already announced that they will no longer enforce their aggregate limits. The Rhode Island State Board of Elections announced that it would support legislation that would repeal the state’s aggregate limit provision, and the Wyoming Legislature is in the process of drafting a bill to repeal its aggregate limit statute for introduction in the 2015 legislative session. Additionally, Wisconsin’s limit has been struck down in Court, and the State of Minnesota has been enjoined by a federal court from enforcing a portion of its “First Come, First Served” statute, as it undergoes a legal challenge.

Three key aspects of the McCutcheon opinion render many of the different forms of aggregate limits harder for states to defend from a challenge in court: (1) the Court appeared to significantly narrow the basis for regulation of contribution limits; (2) McCutcheon clarified that even contribution limits are subject to a high level of constitutional scrutiny; and (3) other language in the Court’s opinion makes it difficult for states to defend aggregate or proportional limits.

Following the actions of the seven states that have already announced non-enforcement of their aggregate limit provisions, policymakers in the District of Columbia and the remaining 12 states with aggregate limits and proportional bans should strongly consider repealing these speech-stifling regulations in order to comply with the precedent set in the McCutcheon decision and avoid a likely successful legal challenge. Additionally, repealing these regulations will also enhance the First Amendment freedoms of the citizens residing in each of these states.

Introduction

On April 2, 2014, the Supreme Court issued its decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission.[1] In that case, plaintiff Shaun McCutcheon challenged the overall federal limits imposed on contributions by individuals to candidate campaigns and political committees instituted as part of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002. These aggregate limits are separate from the individual limits enforced by the federal government and most states on contributions to each candidate, political party committee, or PAC. In the Court’s 5-4 decision, it invalidated the federal aggregate limit as unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

https://www.ifs.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2014-10-22_Issue-Review_McCutcheon_State-Aggregate-Limits-and-Proportional-Bans-Under-McCutcheon.pdf

State Aggregate Limits, Proportional Limits, and Proportional Bans

Much like the federal aggregate limit ruled unconstitutional in McCutcheon, nine states and the District of Columbia impose aggregate limits in some form on the overall amount that entities may contribute to candidates and causes. These limits appear to be clearly unconstitutional, according to the precedent set in McCutcheon.

Another 14 states – four of which also have aggregate limits on individual giving (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Wisconsin) – impose other forms of limits that operate in similar fashion to an aggregate limit, leaving these statutes highly vulnerable to a legal challenge, according to the reasoning in the McCutcheon decision. In an illustration of the overwhelming complexity of campaign finance laws, these other limits fall into seven categories, collectively classified as “proportional limits” or “proportional bans”:

- “First Come, First Served” Limits – the earliest donors to a candidate get to give the maximum allowed by law until a certain aggregate threshold is reached, while later supporters either are banned from donating any amount, must wait to give a donation until other donors make more donations, or face lower donation limits

- Aggregate Limits on Recipient Candidates (Party Version) – candidates face limits on how much they can receive from all political party committees

- Aggregate Limits on Recipient Candidates (PAC Version) – candidates face limits on how much they can receive from all PACs

- Proportional Bans – limits on the amount candidates can receive from certain types of donors relative to their total fundraising

- Non-Resident Aggregate Limits on Candidates, Parties, or PACs – limits on how much or what proportion of an entity’s funds may be donated by non-residents

- Aggregate Limits on PAC Donations – limits on how much each PAC may donate to all candidates, parties, and/or PACs

- Aggregate Limits on Corporate or Union Donations – limits on how much each corporation or union may donate to all candidates and/or political parties

By contrast, the other 31 states do not impose aggregate limits or proportional bans of any kind. Taken together, these 19 states and D.C. with either aggregate limits and/or other limits that are highly vulnerable from the seven categories above are:

Superscript numbers indicate the type of limit, as described in the seven categories above. An asterisk indicates that the state has announced it will no longer enforce some or all of its aggregate limits provisions, or the state lost in court in a challenge to its aggregate limit statute.

As the aggregate limit statutes in nine states and Washington, D.C. function slightly differently, we have summarized the effect of each limit, noted what entities it affects (individuals and/or PACs), and updated each limit’s current status in the following table. (All “Aggregate Limit Descriptions” reflect current state statutes, located in the appendices below. More information on each state’s “Aggregate Limit Status” can be found in the section labeled “State Responses to McCutcheon.”)

|

Nine States and D.C. with Likely Unconstitutional State Aggregate Limits |

|||

|

State |

Entities Affected |

Aggregate Limit Description |

Aggregate Limit Status |

| Connecticut | Individuals PACs |

– An individual may not contribute in excess of $30,000 in the aggregate to all candidates and committees per election cycle- A political committee established by a business entity (“Business PAC”) may not contribute more than $100,000 in the aggregate to all candidates per election cycle- A political committee established by an organization (“Organization PAC”) may not contribute more than $50,000 in the aggregate to all candidates per election cycle | The Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission issued an Advisory Opinion, in which it announced it would no longer enforce Connecticut’s aggregate limit statute on individual giving to all candidates and committees. |

| D.C. | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $8,500 in the aggregate to all candidates and political committees per election | Attorney General Irvin B. Nathan recommended to the City Council that D.C.’s aggregate limit statute should be repealed. The City Council has yet to act on Attorney General Nathan’s recommendation. |

| Kentucky | Individuals PACs |

– An individual may not contribute in excess of the following amounts in the aggregate per year:

– A PAC may not contribute in excess of the following amounts in the aggregate per year:

|

The Kentucky Registry of Election Finance issued an Advisory Opinion indicating that its aggregate limit on individual giving to all PACs would not apply to the requestor. |

| Maine | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $25,000 in the aggregate to all candidates per calendar year | The Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices released a policy statement indicating it will cease enforcement of its aggregate limit for the duration of the 2014 election cycle. Following the 2014 election cycle, the Commission will make a legislative recommendation to the Maine Legislature regarding the statute’s enforceability. |

| Maryland | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $10,000 in the aggregate to all campaign finance entities[2] per election cycle | The Maryland State Board of Elections issued guidance that it would no longer enforce the state’s aggregate limit on individual giving. |

| Massachusetts | Individuals PACs |

– An individual may not contribute in excess of $12,500 in the aggregate to all candidates per calendar year- An individual may not contribute in excess of $5,000 to all committees of a political party per calendar year- A PAC may not contribute in excess of $5,000 to all committees of a political party per calendar year | The Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance announced it will no longer enforce the state’s aggregate limit on individual giving to all candidates. The Office is still reviewing the applicability of the McCutcheon decision to the state’s aggregate limit on individual giving to all committees of a political party. |

| New York | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $150,000 in the aggregate to all candidates and committees per calendar year | The New York State Board of Elections voted unanimously to cease enforcement of the state’s aggregate limit on individual giving. |

| Rhode Island | Individuals PACs |

– An individual may not contribute in excess of $10,000 in the aggregate to all candidates, political parties, and PACs per calendar year- A PAC may not contribute in excess of $25,000 in the aggregate to all candidates, political parties, and PACs per calendar year | The Rhode Island State Board of Elections voted to support legislation that would repeal the state’s aggregate limit on individual giving. The General Assembly has yet to act on the Board’s recommendation. |

| Wisconsin | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $10,000 in the aggregate to all candidates, political parties, and PACs per calendar year | Following the McCutcheon decision, the state of Wisconsin settled a lawsuit and agreed it would no longer enforce its aggregate limit on individual giving. |

| Wyoming | Individuals | – An individual may not contribute in excess of $25,000 in the aggregate to all candidates per two-year period | The Wyoming Legislature’s Joint Corporations, Elections and Political Subdivisions Interim Committee voted to have its staff draft a bill for introduction in the 2015 legislative session that repeals the state’s aggregate limit. |

As the 14 states with other aggregate or proportional limits or bans statutes differ significantly, we have summarized the effect of the regulation and noted what entities it affects (recipient candidates, individuals, political parties, PACs, corporations, and/or unions) in the following table. (All “Aggregate/Proportional Limit/Ban Descriptions” reflect current state statutes, located in the appendices below, unless otherwise noted.)

|

Fourteen States with other Aggregate or Proportional Limits or Bans |

||

|

State |

Entities Affected |

Aggregate/Proportional Limit/Ban Description |

| Alaska | Recipient Candidates Individuals (Non-Residents) Political Parties Groups Nongroup Entities |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from non-residents per calendar year:

– Political parties are prohibited from accepting more than 10% of their total contributions from non-residents per calendar year – Group and nongroup entities are prohibited from accepting more than 10% of their total contributions from non-residents per calendar year |

| Arizona | Recipient Candidates Political Parties |

– Candidates for statewide office may not accept more than $100,110 in the aggregate from all political party committees and political organizations per election[3]– Candidates for legislative office may not accept more than $10,020 in the aggregate from all political party committees and political organizations per election[4] |

| Florida | Recipient Candidates Political Parties |

– Candidates for statewide office may not accept more than $250,000 in the aggregate from all political party committees per election- Candidates for legislative office may not accept more than $50,000 in the aggregate from all political party committees per election |

| Hawaii | Recipient Candidates Individuals (Non-Residents) |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than 30% of their total contributions from non-residents per election period |

| Indiana | Corporations Unions |

– A corporation or labor union may not contribute in excess of the following amounts in the aggregate per calendar year:

– A corporation or labor union may not contribute in excess of $5,000 in the aggregate to all political parties per calendar year |

| Kentucky | Recipient Candidates Political Parties PACs |

– Candidates may not accept more than 50% of their total contributions, or $10,000, whichever is greater, in the aggregate from all political party executive committees per election- Candidates may not accept more than 50% of their total contributions, or $10,000, whichever is greater, in the aggregate from all political party caucus committees per election- Candidates may not accept more than 50% of their total contributions, or $10,000, whichever is greater, in the aggregate from all PACs per election |

| Louisiana | Recipient Candidates PACs |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all PACs per election cycle:

|

| Massachusetts | Recipient Candidates PACs |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all Regular PACs per calendar year:

|

| Minnesota[5] | Recipient Candidates Individuals Political Parties PACs |

– Candidates may not accept more than 20% of the election cycle segment[6] expenditure limits for a specified office in the aggregate from all political committees, political funds, lobbyists, large contributors, and associations, currently[7]:

– Candidates may not accept more than ten times the amount of the base contribution limit for a specified office from all political party committees in the aggregate in an election cycle segment, currently[8]:

|

| Montana | Recipient CandidatesPolitical Parties PACs |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all political party committees per election, currently[9]:

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all PACs per election, currently[10]:

|

| New York | Corporations | – A corporation may not contribute in excess of $5,000 in the aggregate to all candidates per calendar year |

| South Carolina | Recipient Candidates Political Parties |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all political party committees per election cycle:

|

| Tennessee | Recipient Candidates Political Parties PACs |

– Candidates are prohibited from accepting more than the following aggregate amounts from all political party committees per election, currently[11]:

– Candidates for statewide office may not accept more than 50% of their total contributions from all PACs per election – Candidates for legislative office may not accept more than $112,300 in the aggregate from all PACs per election[12] |

| Wisconsin | Political Parties PACs |

– Candidates for state and local office may not accept more than 65% of the state-determined disbursement level[13] for a specified office from all political party committees per election cycle, currently[14]:

– Candidates for state and local office may not accept more than 45% of the state-determined disbursement level for a specified office from all PACs per election cycle, currently[15][16]:

|

State Responses to McCutcheon

Because of the Supreme Court’s ruling in McCutcheon, the aggregate limit statutes in nine states and D.C., in particular, are highly likely to be deemed unconstitutional, if challenged. However, because of the nature of the regulations in the states with proportional limits, those statutes too face an uncertain future.

As a result of the Court’s ruling, all nine states with aggregate limit statutes (and D.C) have already recognized McCutcheon’s applicability to their own law to varying degrees. Seven of these states (Connecticut, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Wisconsin) have effectively officially announced that they will no longer enforce their aggregate limit statutes on individual giving.

On the day of the McCutcheon ruling, the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance announced that it “will no longer enforce the $12,500 aggregate limit on the amount that an individual may contribute to all candidates.”[17] Shortly thereafter, the Maryland State Board of Elections announced that “[t]he [Maryland] Attorney General has advised that based on the pronouncement in the McCutcheon decision, the aggregate contribution limit in [Maryland] Election Law Article § 13-226(b)(2) is unconstitutional and may not be enforced.”[18] As a result of this announcement, much like Massachusetts, the state of Maryland will no longer enforce its $10,000 aggregate limit on what individuals may give to all campaign finance entities per election cycle.

Connecticut’s State Elections Enforcement Commission issued an Advisory Opinion on May 14 noting that it would cease enforcement of its aggregate limit statute.[19] On May 15, the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, Irvin B. Nathan, testified before the City Council, recommending that the District’s aggregate limit provision “is likely unconstitutional and should be considered for repeal.”[20] At a May 22 meeting of the New York State Board of Elections, the Board voted unanimously that the state’s aggregate statue was unenforceable and agreed to cease its enforcement.[21] The Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices announced in a policy statement after their May 28 meeting that it will cease enforcing the state’s aggregate limit for the duration of the 2014 election cycle, and likely permanently thereafter.[22]

On June 5, the Kentucky Registry of Election Finance issued an Advisory Opinion indicating that its aggregate limit on individual giving to all PACs would not apply to the requestor.[23] That same day, the Wyoming Joint Corporations, Elections and Political Subdivisions Interim Committee voted to have its staff draft a bill for introduction in the 2015 legislative session that would repeal the state’s aggregate limit provisions.[24] Similarly, the Rhode Island State Board of Elections voted in April to back legislation that would repeal the state’s aggregate limit provision.[25]

Additionally, Wisconsin had its aggregate limit struck down in Court,[26] and a district judge temporarily blocked the State of Minnesota from enforcing the state’s “first come, first served” limit, which caps the number of contributions candidates may receive from certain classes of donors.[27] It remains to be seen how the court will resolve this case, but, much like in Wisconsin, the Minnesota case has a strong chance of success.

Officials in Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, Montana, South Carolina, and Tennessee have not indicated how they intend to approach their aggregate and/or proportional limit statutes in the wake of the McCutcheon decision.

If other states do not issue similar statements to the eight states and D.C. described above, and any of these state aggregate limits are challenged in similar fashion to Minnesota and Wisconsin’s provisions, it’s highly likely that many, if not all of these aggregate limit statutes, would be eventually subject to a lawsuit and declared unconstitutional, according to the precedent set by the Court in McCutcheon.

The Court clarified in McCutcheon that contribution limits burden the First Amendment freedom of association and can only be justified to the extent they are “the least restrictive means” of preventing quid pro quo corruption – a form of corrupt exchange that goes beyond the mere creation of gratitude. Because the federal aggregate limits went beyond preventing quid pro quo corruption, the Court found aggregate limits to be invalid under the First Amendment. State limits would likely fall under the same rationale. Furthermore, states with proportional bans are also susceptible to legal challenges based upon the Court’s reasoning.

The Impact of McCutcheon

Three key aspects of the McCutcheon opinion make many of the different forms of aggregate limits harder for states to defend from a challenge in court.

1) The Court appeared to significantly narrow the basis for regulation of contribution limits.

According to Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion: “Any regulation must instead target what we have called ‘quid pro quo’ corruption or its appearance. That Latin phrase captures the notion of a direct exchange of an official act for money…. Campaign finance restrictions that pursue other objectives, we have explained, impermissibly inject the Government ‘into the debate over who should govern.’ And those who govern should be the last people to help decide who should govern.”[28]

Later in the opinion, the Court said: “This Court has identified only one legitimate governmental interest for restricting campaign finances: preventing corruption or the appearance of corruption. We have consistently rejected attempts to suppress campaign speech based on other legislative objectives….The First Amendment prohibits such legislative attempts to ‘fine-tun[e]’ the electoral process, no matter how well intentioned.”[29] “As we framed the relevant principle in Buckley, ‘the concept that government may restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.’”[30]

Further addressing the issue of corruption, the opinion states: “Moreover, while preventing corruption or its appearance is a legitimate objective, Congress may target only a specific type of corruption-‘quid pro quo’ corruption…. The definition of corruption that we apply today, however, has firm roots in Buckley itself…. The line between quid pro quo corruption and general influence may seem vague at times, but the distinction must be respected in order to safeguard basic First Amendment rights. In addition, ‘[i]n drawing that line, the First Amendment requires us to err on the side of protecting political speech rather than suppressing it.’”[31]

Clearly, this language in the opinion puts many restrictions on political giving in the form of aggregate or proportional limits on shaky constitutional ground.

2) McCutcheon clarified that even contribution limits are subject to a high level of constitutional scrutiny.

From the opinion: “Moreover, regardless whether we apply strict scrutiny or Buckley‘s ‘closely drawn’ test, we must assess the fit between the stated governmental objective and the means selected to achieve that objective.[32] Or to put it another way, if a law that restricts political speech does not ‘avoid unnecessary abridgement’ of First Amendment rights, it cannot survive ‘rigorous’ review.”[33]

In the opinion, the Court also said: “Importantly, there are multiple alternatives available to Congress that would serve the Government’s anticircumvention interest, while avoiding ‘unnecessary abridgment’ of First Amendment rights.”[34]

What was unusual about this case is that the opinion outlined several examples of how Congress could fashion alternative restrictions to prevent circumvention of the candidate contribution limits. For example, it said: “The most obvious might involve targeted restrictions on transfers among candidates and political committees,” and then listed at least four other less harmful options before concluding that, “[t]he point is that there are numerous alternative approaches available to Congress to prevent circumvention of the base limits.”[35]

If any of the states with these aggregate or proportional limits has any legitimate interest in the limit, then it appears they must show that other remedies that infringe on First Amendment rights to a lesser extent are inadequate to the task.

3) Other language in the Court’s opinion makes it difficult for states to defend aggregate or proportional limits.

There is one quote from the opinion that is very helpful to challenges to these limits: “[W]e have made clear that Congress may not regulate contributions simply to reduce the amount of money in politics, or to restrict the political participation of some in order to enhance the relative influence of others.”[36]

Clearly, many states have done exactly that with their seven varieties of aggregate and proportional limits.

The opinion also states: “An aggregate limit on how many candidates and committees an individual may support through contributions is not a ‘modest restraint’ at all. The Government may no more restrict how many candidates or causes a donor may support than it may tell a newspaper how many candidates it may endorse.”[37]

Presumably, the same logic would apply to many of the proportional limits or to candidates that might wish to receive financial support from more committees.

Additionally, the Court said: “To require one person to contribute at lower levels than others because he wants to support more candidates or causes is to impose a special burden on broader participation in the democratic process…. And as we have recently admonished, the Government may not penalize an individual for ‘robustly exercis[ing]’ his First Amendment rights.”[38]

The same logic that applies to individuals would likely also apply to political committees, which are just associations of individuals, and perhaps political party committees.

Later in the opinion, the Court said, “the degree to which speech is protected cannot turn on a legislative or judicial determination that particular speech is useful to the democratic process. The First Amendment does not contemplate such ‘ad hoc balancing of relative social costs and benefits.”’[39]

If the state had some theory that providing special advantages to earlier donors over later donors or certain types of donors over others, it appears that will no longer save the regulation, if indeed it ever did.

Conclusion

Even before the McCutcheon ruling, states were acting to eliminate aggregate limit statutes, in part due to a growing recognition of their burden on First Amendment rights. In Arizona, for example, Governor Jan Brewer (R) signed a bill into law in April 2013, which raised existing state contribution limits on the amount individuals and PACs may give to candidate campaigns and eliminated Arizona’s aggregate limits on contributions from individuals and PACs to statewide and legislative candidates (though the legislation left intact an aggregate provision limiting candidate receipts from all political party committees), freeing individuals and groups to contribute up to the limit for as many candidates as they wish.

Following Arizona’s example as well as the actions of the seven states that have already announced non-enforcement of their aggregate limit provisions, policymakers in the District of Columbia and the remaining 12 states with aggregate limits and proportional bans should strongly consider repealing these speech-stifling regulations in order to comply with the precedent set in the McCutcheon decision and avoid a likely successful legal challenge. Additionally, repealing these regulations will also enhance the First Amendment freedoms of the citizens residing in each of these states.

Appendix I: Likely Unconstitutional State Aggregate Limit Statutes

For further analysis of each state’s aggregate limit on overall individual giving, this appendix provides the text of and cites to the corresponding statutes of the nine states and the District of Columbia. The following ten aggregate limit statutes are now likely unconstitutional, as they function nearly identically to the federal aggregate limit statute struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in McCutcheon v. FEC.

Connecticut – Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-611(c); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-613(d); Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 9-615(c) and (e)

Sec. 9-611. (c) No individual shall make contributions to such candidates or committees which in the aggregate exceed thirty thousand dollars for any single election and primary preliminary thereto.

Sec. 9-613. (d) Contribution limits for particular offices. A political committee organized by a business entity shall not make a contribution or contributions to or for the benefit of any candidate’s campaign for nomination at a primary or any candidate’s campaign for election to the office of: (1) Governor, in excess of five thousand dollars; (2) Lieutenant Governor, Secretary of the State, Treasurer, Comptroller or Attorney General, in excess of three thousand dollars; (3) state senator, probate judge or chief executive officer of a town, city or borough, in excess of one thousand five hundred dollars; (4) state representative, in excess of seven hundred fifty dollars; or (5) any other office of a municipality not included in subdivision (3) of this subsection, in excess of three hundred seventy-five dollars. The limits imposed by this subsection shall apply separately to primaries and elections and contributions by any such committee to candidates designated in this subsection shall not exceed one hundred thousand dollars in the aggregate for any single election and primary preliminary thereto. Contributions to such committees shall also be subject to the provisions of section 9-618 in the case of committees formed for ongoing political activity or section 9-619 in the case of committees formed for a single election or primary.

Sec. 9-615. (c) The limits imposed by subsection (a) of this section shall apply separately to primaries and elections and no such committee shall make contributions to the candidates designated in this section which in the aggregate exceed fifty thousand dollars for any single election and primary preliminary thereto.

(e) Contributions to a political committee established by an organization shall also be subject to the provisions of section 9-618 in the case of a committee formed for ongoing political activity or section 9-619 in the case of a committee formed for a single election or primary.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

District of Columbia – DC Off. Code § 1-1131.01

No person may make contributions in any one election, for the Mayor, Shadow Senator or Shadow Representative, the Chairman of the Council, any member of the Council and each member of the Board of Education (including primary and general elections, but excluding special elections) which, when totaled with all other contributions made by that person in that election to candidates and political committees, exceeds the total sum of $8500.00.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kentucky – Ky. Rev. Stat. § 121.150(10)

(10) No person shall contribute more than one thousand five hundred dollars ($1,500) to all permanent committees and contributing organizations in any one (1) year.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Maine – Me. Rev. Stat. Ann., Tit. 21–A, § 1015(3)

3. No individual may make contributions to candidates aggregating more than $25,000 in any calendar year. This limitation does not apply to contributions in support of a candidate by that candidate or that candidate’s spouse or domestic partner.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Maryland – Md. Elec. Law Code Ann. § 13–226(b)(2)

(b) Subject to subsection (c) of this section, a person may not, either directly or indirectly, in an election cycle make aggregate contributions in excess of:

(2) $10,000 to all campaign finance entities.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Massachusetts – Mass. Gen. Laws, ch. 55, §§ 7A(a)(2) and (5)

Section 7A. (a)(2) An individual may in addition make campaign contributions for the benefit of elected political committees or non-elected political committees organized on behalf of a political party; provided, however, that the aggregate of such campaign contributions for the benefit of the political committees of any one political party shall not exceed in any one calendar year the sum of five thousand dollars.

[…]

(5) Notwithstanding any other provision of this subsection, the aggregate of all contributions from any one individual to all candidates and candidate’s committees shall not exceed the sum of twelve thousand five hundred dollars in any one calendar year.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

New York – N.Y. Elec. Law § 14–114(8)

Sec. 14–114. 8. Except as may otherwise be provided for a candidate and his family, no person may contribute, loan or guarantee in excess of one hundred fifty thousand dollars within the state in connection with the nomination or election of persons to state and local public offices and party positions within the state of New York in any one calendar year. For the purposes of this subdivision ‘‘loan’’ or ‘‘guarantee’’ shall mean a loan or guarantee which is not repaid or discharged in the calendar year in which it is made.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Rhode Island – R. I. Gen. Laws § 17–25–10.1(a)(1)

(a)(1) No person, other than the candidate to his or her own campaign, nor any political action committee shall make a contribution or contributions to any candidate, as defined by § 17-25-3, or political action committee or political party committee which in the aggregate exceed one thousand dollars ($1,000) within a calendar year, nor shall any person make contributions to more than one state or local candidate, to more than one political action committee, or to more than one political party committee, or to a combination of state and local candidates and political action committees and political party committees which in the aggregate exceed ten thousand dollars ($10,000) within a calendar year, nor shall any political action committee make such contributions which in the aggregate exceed twenty-five thousand dollars ($25,000) within a calendar year, nor shall any candidate or any political action committee or any political party committee accept a contribution or contributions which in the aggregate exceed one thousand dollars ($1,000) within a calendar year from any one person or political action committee.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Wisconsin – Wis. Stat. § 11.26(4)

(4) No individual may make any contribution or contributions to all candidates for state and local offices and to any individuals who or committees which are subject to a registration requirement under s. 11.05, including legislative campaign committees and committees of a political party, to the extent of more than a total of $10,000 in any calendar year.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Wyoming – Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 22–25–102(c)(ii)

(c) Except as otherwise provided in this section, no individual other than the candidate, or the candidate’s immediate family shall contribute directly or indirectly:

(ii) Total political contributions for any two (2) year period consisting of a general election year and the preceding calendar year, of more than twenty-five thousand dollars ($25,000.00).

Appendix II: Highly Vulnerable State Aggregate Limit, Proportional Limit, or Proportional Ban Statutes

For further analysis of each state’s proportional limit or proportional ban statutes, this appendix provides the text of and cites to the corresponding statutes of the fourteen states with these regulations that are highly vulnerable to a legal challenge, pursuant to the Supreme Court’s decision in McCutcheon v. FEC. While the following fourteen statutes function somewhat differently than the federal aggregate limits ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, they are ripe for legal challenge, and may also be considered unconstitutional.

Alaska – Alaska Stat. §§ 15.13.072(e), (f), and (h)

(e) A candidate or an individual who has filed with the commission the document necessary to permit that individual to incur election-related expenses under AS 15.13.100 may solicit or accept contributions from an individual who is not a resident of the state at the time the contribution is made if the amounts contributed by individuals who are not residents do not exceed

(1) $20,000 a calendar year, if the candidate or individual is seeking the office of governor or lieutenant governor;

(2) $5,000 a calendar year, if the candidate or individual is seeking the office of state senator;

(3) $3,000 a calendar year, if the candidate or individual is seeking the office of state representative or municipal or other office.

(f) A group or political party may solicit or accept contributions from an individual who is not a resident of the state at the time the contribution is made, but the amounts accepted from individuals who are not residents may not exceed 10 percent of total contributions made to the group or political party during the calendar or group year in which the contributions are received.

[…]

(h) A nongroup entity may solicit or accept contributions for the purpose of influencing the nomination or election of a candidate from an individual who is not a resident of the state at the time the contribution is made or from an entity organized under the laws of another state, resident in another state, or whose participants are not residents of this state at the time the contribution is made. The amounts accepted by the nongroup entity from these individuals and entities for the purpose of influencing the nomination or election of a candidate may not exceed 10 percent of total contributions made to the nongroup entity for the purpose of influencing the nomination or election of a candidate during the calendar year in which the contributions are received.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Arizona – Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 16-905(D)

D. A nominee of a political party shall not accept contributions from all political parties or political organizations combined totaling more than ten thousand twenty dollars for an election for an office other than a statewide office, and one hundred thousand one hundred ten dollars for an election for a statewide office.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Florida – Fla. Stat. § 106.08(2)

(2)(a) A candidate may not accept contributions from national, state, or county executive committees of a political party, including any subordinate committee of such political party or affiliated party committees, which contributions in the aggregate exceed $50,000.

(b) A candidate for statewide office may not accept contributions from national, state, or county executive committees of a political party, including any subordinate committee of the political party, or affiliated party committees, which contributions in the aggregate exceed $250,000…

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hawaii – Haw. Rev. Stat. § 11-362(a)

(a) Contributions from all persons who are not residents of the State at the time the contributions are made shall not exceed thirty per cent of the total contributions received by a candidate or candidate committee for each election period.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Indiana – Ind. Code § 3-9-2-4

IC 3-9-2-4. Corporations or labor organizations; limitation on contributions

Sec. 4. During a year a corporation or labor organization may not make total contributions in excess of:

(1) an aggregate of five thousand dollars ($5,000) apportioned in any manner among all candidates for state offices (including a judge of the court of appeals whose retention in office is voted on by a district that does not include all of Indiana);

(2) an aggregate of five thousand dollars ($5,000) apportioned in any manner among all state committees of political parties;

(3) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among all candidates for the senate of the general assembly;

(4) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among all candidates for the house of representatives of the general assembly;

(5) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among regular party committees organized by a legislative caucus of the senate of the general assembly;

(6) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among regular party committees organized by a legislative caucus of the house of representatives of the general assembly;

(7) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among all candidates for school board offices and local offices; and

(8) an aggregate of two thousand dollars ($2,000) apportioned in any manner among all central committees other than state committees.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kentucky – Ky. Rev. Stat. § 121.150(23)

(23) (a) A candidate or a slate of candidates for elective public office shall not accept contributions from permanent committees which, in the aggregate, exceed fifty percent (50%) of the total contributions accepted by the candidate or a slate of candidates in any one (1) election or ten thousand dollars ($10,000) in any one (1) election, whichever is the greater amount. The percentage of the total contributions or dollar amounts of contributions accepted by a candidate or a slate of candidates in an election that is accepted from permanent committees shall be calculated as of the day of each election. Funds in a candidate’s or a slate of candidates’ campaign account which are carried forward from one (1) election to another shall not be considered in calculating the acceptable percentage or dollar amount of contributions which may be accepted from permanent committees for the election for which the funds are carried forward. A candidate or a slate of candidates may, without penalty, contribute funds to his campaign account not later than sixty (60) days following the election so as not to exceed the permitted percentage or dollar amount of contributions which may be accepted from permanent committees or the candidate or a slate of candidates may, not later than sixty (60) days after the end of the election, refund any excess permanent committee contributions on a pro rata basis to the permanent committees whose contributions are accepted after the aggregate limit has been reached.

(b) The provisions of paragraph (a) of this subsection regarding the receipt of aggregate contributions from permanent committees in any one (1) election shall also apply separately to the receipt of aggregate contributions from executive committees of any county, district, state, or federal political party in any one (1) election.

(c) The provisions of paragraph (a) of this subsection regarding the receipt of aggregate contributions from permanent committees in any one (1) election shall also apply separately to the receipt of aggregate contributions from caucus campaign committees.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Louisiana – La. Rev. Stat. § 18:1505.2 H.(7)

(7)(a) The total amount of combined contributions for both the primary and general elections, from political committees, which may be accepted by a candidate and his principal and subsidiary campaign committees, shall not exceed the following aggregate amounts:

(i) Major office candidates – eighty thousand dollars.

(ii) District office candidates – sixty thousand dollars.

(iii) Other office candidates – twenty thousand dollars.

(b) The provisions of this Paragraph shall not apply to contributions made by a recognized political party or any committee thereof.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Massachusetts – Mass. Gen. Laws, ch. 55, § 6A

Section 6A. A candidate and such candidate’s committee shall not accept any contribution from a political action committee if such contribution would result in such candidate and such committee together receiving from all political action committees aggregate contributions in any calendar year in excess of the following amounts:

(a) a candidate for governor, including contributions jointly to such candidate for governor and a candidate for lieutenant governor in a state election—one hundred and fifty thousand dollars;

(b) a candidate for lieutenant governor—thirty-one thousand, two hundred and fifty dollars;

(c) a candidate for attorney general—sixty-two thousand, five hundred dollars;

(d) a candidate for state secretary, state treasurer, and state auditor—thirty-seven thousand, five hundred dollars;

(e) a candidate for state senator, county commissioner, governor’s councillor, district attorney, clerk of courts, register of probate, registrar of deeds or any other county officer—eighteen thousand, seven hundred and fifty dollars;

(f) a candidate for state representative—seven thousand, five hundred dollars.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Minnesota – Minn. Stat. §§ 10A.27, Subds. 2 and 11

Subd. 2. A candidate must not permit the candidate’s principal campaign committee to accept contributions from any political party units or dissolving principal campaign committees in aggregate in excess of ten times the amount that may be contributed to that candidate as set forth in subdivision 1. The limitation in this subdivision does not apply to a contribution from a dissolving principal campaign committee of a candidate for the legislature to another principal campaign committee of the same candidate.

Subd. 11. A candidate must not permit the candidate’s principal campaign committee to accept a contribution from a political committee, political fund, lobbyist, large contributor, or association not registered with the board if the contribution will cause the aggregate contributions from those types of contributors during an election cycle segment to exceed an amount equal to 20 percent of the election cycle segment expenditure limits for the office sought by the candidate, provided that the 20 percent limit must be rounded to the nearest $100. For purposes of this subdivision, “large contributor” means an individual, other than the candidate, who contributes an amount that is more than one-half the amount an individual may contribute during the election cycle segment.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Montana – Mont. Code Ann. §§ 13-37-216(3) and (4); Mont. Code Ann. § 13-37-218

Sec. 13-37-216. (3) All political committees except those of political party organizations are subject to the provisions of subsections (1) and (2). For purposes of this subsection, “political party organization” means any political organization that was represented on the official ballot at the most recent gubernatorial election. Political party organizations may form political committees that are subject to the following aggregate limitations, adjusted as provided for in subsection (4) and subject to 13-37-219, from all political party committees:

(a) for candidates filed jointly for the offices of governor and lieutenant governor, not to exceed $18,000;

(b) for a candidate to be elected for state office in a statewide election, other than the candidates for governor and lieutenant governor, not to exceed $6,500;

(c) for a candidate for public service commissioner, not to exceed $2,600;

(d) for a candidate for the state senate, not to exceed $1,050;

(e) for a candidate for any other public office, not to exceed $650.

(4) (a) The commissioner shall adjust the limitations in subsections (1) and (3) by multiplying each limit by an inflation factor, which is determined by dividing the consumer price index for June of the year prior to the year in which a general election is held by the consumer price index for June 2002.

(b) The resulting figure must be rounded up or down to the nearest:

(i) $10 increment for the limits established in subsection (1); and

(ii) $50 increment for the limits established in subsection (3).

(c) The commissioner shall publish the revised limitations as a rule.

Sec. 13-37-218. A candidate for the state senate may receive no more than $ 2,150 in total combined monetary contributions from all political committees [PACs] contributing to the candidate’s campaign, and a candidate for the state house of representatives may receive no more than $ 1,300 in total combined monetary contributions from all political committees [PACs] contributing to the candidate’s campaign. The limitations in this section must be multiplied by an inflation factor, which is determined by dividing the consumer price index for June of the year prior to the year in which a general election is held by the consumer price index for June 2003. The resulting figure must be rounded up or down to the nearest $50 increment. The commissioner shall publish the revised limitations as a rule….

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

New York – N.Y. Elec. Law § 14–116(2)

Sec. 14–116. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of subdivision one of this section, any corporation or an organization financially supported in whole or in part, by such corporation may make expenditures, including contributions, not otherwise prohibited by law, for political purposes, in an amount not to exceed five thousand dollars in the aggregate in any calendar year; provided that no public utility shall use revenues received from the rendition of public service within the state for contributions for political purposes unless such cost is charged to the shareholders of such a public service corporation.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

South Carolina – S.C. Code § 8-13-1316(A)

(A) Notwithstanding Section 8-13-1314(A)(1), within an election cycle, a candidate may not accept or receive contributions from a political party through its party committees or legislative caucus committees, and a political party through its party committees or legislative caucus committees may not give to a candidate contributions which total in the aggregate more than:

(1) fifty thousand dollars in the case of a candidate for statewide office; or

(2) five thousand dollars in the case of a candidate for any other office.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tennessee – Tenn. Code §§ 2-10-302(c) and (d); Tenn. Code §§ 2-10-306(a) and (c)

Sec. 2-10-302. (c) With respect to contributions from multicandidate political campaign committees for each election:

(1) No candidate for an office elected by statewide election shall accept in the aggregate more than fifty percent (50%) of the candidate’s total contributions from multicandidate political campaign committees; and

(2) No candidate for any other state or local public office shall accept in the aggregate more than seventy-five thousand dollars ($75,000) from multicandidate political campaign committees.

In determining the aggregate limits established by this subsection (c), contributions made to a candidate by a committee controlled by a political party on the national, state, or local level or by a caucus of such political party established by members of either house of the general assembly are not included.

(d) (1) Each contribution limit established in subsection (a), (b) or (c) shall be adjusted to reflect the percentage of change in the average consumer price index (all items-city average), as published by the United States department of labor, bureau of labor statistics, for the period of January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2010. Each such adjustment shall be rounded to the nearest multiple of one hundred dollars ($100). The registry of election finance shall publish each such adjusted amount on its web site.

(2) On January 1, 2013, and every two (2) years thereafter, each contribution limit established in subsection (a), (b) or (c), as adjusted pursuant to subdivision (d)(1), shall be further adjusted to reflect the percentage of change in the average consumer price index (all items-city average), as published by the United States department of labor, bureau of labor statistics, for the two-year period immediately preceding. Each such adjustment under this subdivision (d)(2) shall be rounded to the nearest multiple of one hundred dollars ($100). The registry of election finance shall publish each such adjusted amount on its web site.

Sec. 2-10-306. (a) All contributions made by political campaign committees controlled by a political party on the national, state, or local level or by a caucus of such political party established by members of either house of the general assembly shall be considered to have been made by a single committee. Such contributions shall not, in the aggregate, exceed:

(1) Two hundred fifty thousand dollars ($250,000) per election to any candidate in a statewide election;

(2) Forty thousand dollars ($40,000) per election to any candidate for the senate; and

(3) Twenty thousand dollars ($20,000) per election to any candidate for any other state or local public office.

[…]

(c) (1) Each contribution limit established in subsection (a) shall be adjusted to reflect the percentage of change in the average consumer price index (all items-city average), as published by the United States department of labor, bureau of labor statistics, for the period of January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2010. Each such adjustment shall be rounded to the nearest multiple of one hundred dollars ($100). The registry of election finance shall publish each such adjusted amount on its web site.

(2) On January 1, 2013, and every two (2) years thereafter, each contribution limit established in subsection (a), as adjusted pursuant to subdivision (c)(1), shall be further adjusted to reflect the percentage of change in the average consumer price index (all items-city average), as published by the United States department of labor, bureau of labor statistics, for the two-year period immediately preceding. Each such adjustment under this subdivision (c)(2) shall be rounded to the nearest multiple of one hundred dollars ($100). The registry of election finance shall publish each such adjusted amount on its web site.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Wisconsin – Wis. Stat. § 11.26(9)

(9) (a) No individual who is a candidate for state or local office may receive and accept more than 65 percent of the value of the total disbursement level determined under s. 11.31 for the office for which he or she is a candidate during any primary and election campaign combined from all committees subject to a filing requirement, including political party and legislative campaign committees.

(b) No individual who is a candidate for state or local office may receive and accept more than 45 percent of the value of the total disbursement level determined under s. 11.31 for the office for which he or she is a candidate during any primary and election campaign combined from all committees other than political party and legislative campaign committees subject to a filing requirement.

[1] 572 U.S. __, No. 12-536 (April 2, 2014).

[2] A “campaign finance entity” means a political committee registered in the state of Maryland. Md. Elec. Law Code Ann. § 1-101(h).

[3] Pursuant to Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 16-941(B), the statutory aggregate limits in this section are reduced by 20 percent for statewide candidates who choose not to participate in Arizona’s Clean Elections program. According to the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office, nonparticipating statewide candidates may receive $91,040 in the aggregate from all political party committees and political organizations in the 2014 election. See Secretary of State Ken Bennett, “Campaign Contribution Limits 2014 General Election: Revised pursuant to Laws 2013, Chapter 98,” State of Arizona Secretary of State. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.azsos.gov/election/2014/info/campaign_contribution_limits.pdf (January 29, 2014), p. 2.

[4] Pursuant to Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 16-941(B), the statutory aggregate limits in this section are reduced by 20 percent for legislative candidates who choose not to participate in Arizona’s Clean Elections program. According to the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office, nonparticipating legislative candidates may receive $9,112 in the aggregate from all political party committees and political organizations in the 2014 election. See Secretary of State Ken Bennett, “Campaign Contribution Limits 2014 General Election: Revised pursuant to Laws 2013, Chapter 98,” State of Arizona Secretary of State. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.azsos.gov/election/2014/info/campaign_contribution_limits.pdf (January 29, 2014), p. 2.

[5] Minnesota’s aggregate limit on candidate receipts from all political committees, political funds, lobbyists, large contributors, and associations is currently being challenged by the Institute for Justice’s Minnesota Chapter. On May 19, 2014, U.S. District Judge Donovan W. Frank enjoined the State of Minnesota from enforcing this statute and ruled that the plaintiffs had a “substantial likelihood of success on the merits of their claim.” The State of Minnesota has yet to appeal the case as of July 8, 2014. For more information, see “Minnesota Campaign Speech Limits: Seaton v. Wiener,” Institute for Justice. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: https://www.ij.org/mn-special-sources-limit (2014).

[6] An “election cycle segment” is “the period from January 1 following a general election for an office to December 31 following the next general election for that office, except that ‘election cycle’ for a special election means the period from the date the special election writ is issued to 60 days after the special election is held. For a regular election, the period from January 1 of the year prior to an election year through December 31 of the election year is the ‘election segment’ of the election cycle. Each other two-year segment of an election cycle is a ‘nonelection segment’ of the election cycle. An election cycle that consists of two calendar years has only an election segment. The election segment of a special election cycle includes the entire special election cycle.” Minn. Stat. § 10A.01, Subd. 16.

[7] Current office-specific aggregate contribution limit information available at: “2013-2014 Election Cycle Segment Contribution and Campaign Expenditure Limits,” Minnesota Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.cfboard.state.mn.us/campfin/Limits/CONTRIB_LIMITS_2013_2014.pdf (January 1, 2013), p. 2. More information about the office-specific expenditure limits relevant to this regulation can be found in Minn. Stat. § 10A.25.

[8] Ibid, p. 1.

[9] Current office-specific aggregate contribution limit information available at: “State of Montana Political Campaign Contribution Limit Summary – applicable to 2014 campaigns,” Montana Commissioner of Political Practices. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://politicalpractices.mt.gov/content/5campaignfinance/2014ContributionLimitSummary (March 19, 2014).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Current office-specific political party aggregate contribution limit information available at: “PAC FAQs,” Tennessee Bureau of Ethics and Campaign Finance. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.tennessee.gov/tref/pacs/pacs_faq.htm#12 (2010).

[12] Current office-specific PAC contribution limit information available at: “PAC FAQs,” Tennessee Bureau of Ethics and Campaign Finance. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.tennessee.gov/tref/pacs/pacs_faq.htm#12 (2010).

[13] The “state determined disbursement level” is calculated on an office-specific basis, pursuant to Wis. Stat. § 11.31(1).

[14] Current office-specific aggregate contribution limit information available at: “Contribution Limits: Partisan State Offices,” Wisconsin Government Accountability Board. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://gab.wi.gov/sites/default/files/page/campaign_contribution_limits_partisan_state_pdf_13605.pdf (June 10, 2013).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Wisconsin’s aggregate limit on candidate receipts from all political committees is currently being challenged by the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty. The lawsuit was filed in on June 23, 2014 in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin. For more information, see Bruce Vielmetti, “Political action group sues over Wisconsin campaign money limits,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.jsonline.com/news/statepolitics/political-action-group-sues-over-over-wisconsin-campaign-money-limits-b99297241z1-264267521.html (June 23, 2014).

[17] “OCPF’s statement on today’s Supreme Court decision, McCutcheon vs. FEC,” Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.ocpf.net/releases/statement.pdf (April 2, 2014).

[18] Bobbie S. Mack et al., “Contribution Limits,” Maryland State Board of Elections. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://elections.maryland.gov/campaign_finance/documents/aggregate_limits_04112014_final.pdf (April 11, 2014).

[19] Anthony J. Castagno, “ADVISORY OPINION 2014-03: Application and Enforcement of Connecticut’s Aggregate Contribution Limits from Individuals to Candidates and Committees after McCutcheon,” State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.ct.gov/seec/lib/seec/laws_and_regulations/ao_2014-03.pdf (May 14, 2014).

[20] Attorney General Irvin B. Nathan, “Letter to David Keating Re: McCutcheon v. FEC and its effect on District law,” Office of the Attorney General of the District of Columbia (May 21, 2014).

[21] Michael Gormley, “State: No limit on individual political donations,” Newsday. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.newsday.com/long-island/politics/state-no-limit-on-individual-political-donations-1.8186788 (May 26, 2014).

[22] “Policy Statement of the Maine Ethics Commission on Enforceability of Aggregate Contribution Limits,” State of Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/ethics/pdf/ProposedStatementNottoEnforceAggLimit.pdf (2014).

[23] Emily Dennis, “ADVISORY OPINION 2014-003,” Kentucky Registry of Election Finance. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://kref.ky.gov/Contributions/2014_003_Opinion.pdf (June 5, 2014).

[24] Laura Hancock, “Wyoming lawmakers want to repeal caps to PAC spending,” Casper Star-Tribune. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://trib.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/wyoming-lawmakers-want-to-repeal-caps-to-pac-spending/article_9a4c8196-d5ff-5eb3-a99b-a53214e8e8d7.html (June 6, 2014).

[25] Michael P. McKinney, “R.I. Board of Elections backs repeal of ‘total’ campaign contribution limit,” Rhode Island Providence Journal. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.providencejournal.com/breaking-news/content/20140417-r.i.-board-of-elections-backs-repeal-of-total-campaign-contribution-limit.ece (April 17, 2014).

[26] Scott Bauer, “Deal reached to kill campaign funding limits,” The Associated Press. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2014/may/8/deal-reached-to-kill-wisconsin-campaign-limits/ (May 8, 2014).

[27] Devin Henry, “Judge halts Minnesota campaign finance law,” MinnPost. Retrieved on July 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.minnpost.com/effective-democracy/2014/05/judge-halts-minnesota-campaign-finance-law (May 19, 2014).

[28] McCutcheon v. Federal Election Comm’n, 572 U.S. __, No. 12-536 slip op. at 3 (2014) (Roberts, C.J. for the plurality) (emphasis added).

[29] Ibid. at 18. (citing Davis v. Federal Election Comm’n, 554 U. S. 724, 741 (2008); Federal Election Comm’n v. National Conservative Political Action Comm., 470 U. S. 480, 496-97 (1985); and Arizona Free Enterprise Club’s Freedom Club PAC v. Bennett, 564 U. S. ___, No. 10-238 slip op. at 21 (2011)).

[30] Ibid. (quoting Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S., 1, 48-49 (1976)).

[31] Ibid. at 19-20 (discussing Buckley, 424 U.S. at 26-27 and quoting Federal Election Comm’n v. Wisconsin Right to Life, 551 U.S. 449, 457 (2007) (“WRTL II”)) (opinion of Roberts, C. J.).

[32] See, e.g., National Conservative Political Action Comm., 470 U. S. at 496-501; Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230, 253-262 (2006) (opinion of Breyer, J.).

[33] McCutcheon at 20. (citing Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. at 25).

[34] Ibid. at 33.

[35] Ibid. at 33-35.

[36] Ibid. at 1 (emphasis added).

[37] Ibid. at 15.

[38] Ibid. at 16 (citing Davis v. Federal Election Comm’n, 554 U. S. 724, 739 (2008)) (emphasis added).

[39] Ibid. at 17 (citing United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 460, 470 (2010); see also United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group, Inc., 529 U.S. 803, 818 (2000) (“‘What the Constitution says is that’ value judgments ‘are for the individual to make, not for the Government to decree, even with the mandate or approval of a majority’”)).