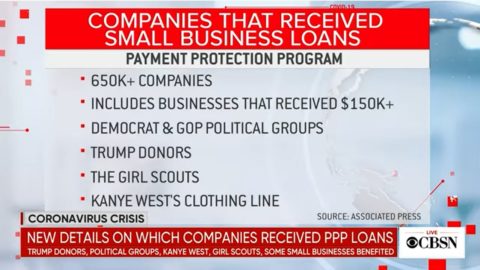

Many are questioning the nature of the loans disbursed by the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) after it was discovered that businesses owned by Trump donors comprised several of the program’s earliest recipients. As the Associated Press noted, “There is no evidence the companies received favorable treatment as a result of their ties to Trump, and the businesses account for just a fraction of the overall spending under the program.” Yet we’ve seen headlines like “Millions in coronavirus aid went to major Trump donors” that don’t make the situation seem nearly as innocuous.

I’m hard-pressed to think of a reason such a story would even exist absent the implication of corruption. Given Trump’s large network of supporters and the vast number of PPP loan recipients, of course those two groups overlap in some capacity. That seems like a basic matter of probability, not a scandal.

Instead, businesses are being suspected of profiting from a corrupt relationship with the government based on nothing but their owners’ political support. (Keep in mind that federal law prohibits the corporations themselves from contributing to candidates and political parties.) Even though there is no evidence for the claim, some in the media have managed to turn a story about nothing into a conspiracy. And they’ve done so by taking advantage of existing donor disclosure laws, which supporters allege improve voter knowledge, but so often become fodder for misleading narratives.

Some have an itch to require disclosure for everything, to trace every dollar as far as possible, but that policy has major downsides (like creating suspicion out of thin air). But what if a politician did want to pad their supporters’ pocketbooks and funnel money to their political allies, while punishing their opposition? It seems odd to provide them with a detailed catalog of every contribution to every candidate – complete with the donor’s name, address, occupation, and employer.

While some may have faith in disclosure laws’ ability to pinpoint instances of favoritism, despite the lack of evidence that such laws improve perceptions of government, perhaps it would be better yet if not even politicians knew who was supporting whom, or how much they had donated. How can you favor your donors – or punish the opposition – if you don’t know who they are?

While there is currently no serious effort to end disclosure of campaign giving, it’s an intriguing idea that could have positive effects on democracy.

1) Donor anonymity could tremendously increase the willingness of Americans to engage in the democratic process.

At any moment, your donation history to political groups and candidates can be viewed by government officials, current or prospective employers, activists, your child’s teacher, or even your neighbors and acquaintances. Thanks to online databases, this information can be accessed in just a few clicks. If they didn’t already know before, they could find out who you are, who you work for, and who you support. If that’s not enough to drastically diminish people’s willingness to support their favored candidates, I’m not sure what would be.

Donor disclosure laws subject supporters to harassment, risk individuals implicating their employer in personal political decisions, and demand that donors sacrifice their right to privacy in exchange for their right to be a political advocate. It’s the reason you vote in a private booth – so you don’t have to answer to the strangers in line behind you who saw which buttons you pressed. With that much pressure, you might wonder who would vote at all.

2) Donor anonymity could bring campaign finance law more in line with First Amendment values and proponents’ stated anti-corruption goals.

Although disclosure mandates have been generally upheld by the Supreme Court in certain circumstances, donor disclosure laws restrict freedom of association and chill freedom of speech. While the government has an interest in preventing corruption, it isn’t clear that donor disclosure laws are successful in this endeavor. As shown with the PPP loans, disclosure can lead to the appearance of corruption even where no corruption exists. And if a public official abuses disclosure reports to decide who to favor and who to disfavor, the law becomes a tool for corruption instead of anti-corruption. Too often, courts have blessed restrictions on speech in exchange for anti-corruption benefits that do not come to fruition.

3) Donor anonymity could help stymie attempts at favoritism.

One of the major goals of campaign finance law is to prevent corrupt exchanges that benefit a politician’s supporters. Yet by favoring donor disclosure too intensely, we may create the scenario we fear. Armed with complete information on their campaign donors, we can never be certain that an elected official isn’t keeping donors’ pocketbooks in mind when they make policy decisions. What is meant to prevent corruption has the potential to do the exact opposite, and in fact, could facilitate corrupt dealing quite easily.

* * *

The baseless suspicions about the PPP loans illustrate disclosure’s inability to properly inform, and they illuminate disclosure’s potential to enable actual corruption in the future. If we are truly concerned with promoting political advocacy, maximizing First Amendment freedoms, and combating corruption, we may want to consider implementing greater degrees of donor privacy in our laws.