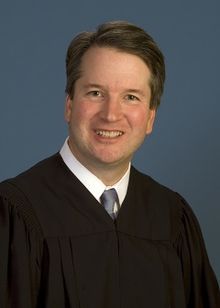

When Justice Kennedy announced his retirement from the Supreme Court last month, the Institute for Free Speech conducted a thorough review of the First Amendment records of each of the potential nominees for the seat on the President’s shortlist, with an emphasis on political speech.[1] Judge Brett Kavanaugh, the eventual nominee, had the longest record of any of the suspected finalists for the nomination.

We noted a number of decisions in which we disagree with Judge Kavanaugh. These included Holmes v. Federal Election Commission, a case in which we represented the plaintiffs, but Judge Kavanaugh joined an opinion by Obama appointee Sri Srinivasan upholding an FEC regulation that had the practical effect of giving many incumbents higher contribution limits than their challengers;[2] and Wagner v. Federal Election Commission, in which Judge Kavanaugh joined a majority in voting to uphold a ban on political contributions by individuals who held government contracts, and where we filed an amicus brief on the losing side.[3]

Nevertheless, we concluded – as did most others specifically looking at Judge Kavanaugh’s record in First Amendment cases, that he generally gave the First Amendment a robust interpretation protective of individual rights, and we offered praise for his nomination.

The Campaign Legal Center (CLC) was founded in 2002 with a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts as an organization “dedicated to protecting and implementing” restraints on political contributions and spending. In the years since, through legal briefs, testimony in Congress and at the Federal Election Commission, complaints filed with public agencies, reports, and op-eds, CLC has been a tireless and often effective advocate for more regulation of political speech and the political process. So, it is not surprising that if the Institute for Free Speech and other First Amendment advocates like the Kavanaugh nomination, CLC does not.

What is unfortunate is that CLC has chosen to make the case for its opposition to Kavanaugh through a report that alternately misleads, misrepresents, cherry-picks data, and resorts to alarmism in place of serious analysis. Titled “Kavanaugh Has an Unsettling Record on Democracy,”[4] and released as a joint effort with the left-wing group Demos,[5] the report does no credit to CLC, and perhaps indicates the general lack of any serious basis for attacking the Kavanaugh nomination. In this review, I will go through the CLC charges as they are presented in the report.

Judge Kavanaugh on Presidential Power

Oddly, CLC’s report begins, not with anything directly related to campaigns or speech, but with a brief discussion of Judge Kavanaugh’s purported views on presidential power. This brief section merely recites what has become a talking point for certain anti-Kavanaughistas – that, if seated, he will allow President Trump to skate for whatever nefarious deeds might eventually come before the Supreme Court.[6]

The basis for this claim is a law review article and speech that Judge Kavanaugh made in 2009, at the beginning of the Obama presidency, arguing that presidents should not be subject to prosecution or civil suits while in office. (They are obviously, Kavanaugh notes, subject to impeachment proceedings while in office.) In the law review article, Judge Kavanaugh urges Congress to pass a law exempting the president, while in office, from prosecution. Note that by suggesting Congress should pass a law exempting the president from prosecution, Judge Kavanaugh was implicitly agreeing that, under the Constitution and existing law, the president can be so prosecuted, or that, at the least, it is an open question. Further, he makes clear that such a statute would not relieve a president of civil or criminal liability, but merely postpone it until after the president leaves office – voluntarily, due to the end of the term, or due to impeachment.[7]

Brookings Fellow Ben Wittes and Harvard Law Professor Noah Feldman, both vociferous critics of President Trump, have knocked this claim out of the park, and I will direct readers there. As Professor Feldman sums up, “properly understood, Kavanaugh’s expressed views actually support the opposite conclusion” of that argued by CLC and Demos – they support the conclusion “that the president can be investigated and maybe even indicted unless Congress passes a law saying he can’t – which Congress has not done.” Indeed, Feldman goes on to note that Kavanaugh is actually more open to a possible indictment of the President than most scholars, writing, “many, probably most constitutional scholars think a sitting president can’t be indicted.” As for Mr. Wittes, he concludes, “In some respects, [Feldman] actually understates the case” for Kavanaugh, and against CLC’s interpretation.

CLC’s decision to comment outside its wheelhouse is puzzling, and perhaps this component of the report was either at the insistence of, or written by, CLC’s partners at Demos.

Money in Politics

After this brief opening detour into conspiratorial swamps, the CLC report gets down to business. And what business! It starts with four bullet points that CLC claims demonstrate Judge Kavanaugh’s “radical deregulatory impulses.”[8] What are they, exactly?

The first is that Judge Kavanaugh believes that money is “the equivalent of speech; thus, the contribution and expenditure of money requires the same constitutional protections as other political speech.” (The quoted language is CLC’s, not Judge Kavanaugh’s). How radical is this? Every sitting justice on the Supreme Court, including Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan, agrees that limits on money in politics limit speech and invoke First Amendment protection, the same as other political speech.[9] Moreover, the Supreme Court has recognized that restrictions on political contributions and expenditures raise First Amendment issues for literally decades.[10] Indeed, this has been the position of every Supreme Court Justice of the last 40-plus years with the sole exception of Justice Stevens.[11] The dispute among the justices is not over whether political spending and contributions bring the First Amendment into play, but the degree to which the limitations burden speech and whether or not the government has a compelling interest in regulating that speech that overcomes the First Amendment objection. Judge Kavanaugh’s recognition of the First Amendment interests at stake, far from being radical, is the view of every Justice on the Court.

CLC’s second bullet is that Judge Kavanaugh believes that only “quid pro quo corruption and its appearance” constitutes a compelling government interest to justify the First Amendment burdens imposed by campaign finance regulation.[12] This, too, is already the long-standing majority position on the Supreme Court.[13]

Third, CLC cites as radical Judge Kavanaugh’s view that “SuperPAC and other ‘independent’ spending limits cannot be justified by the interest in preventing corruption.”[14] Where SuperPACs are concerned, this is not only the position of Judge Kavanaugh – it was the position of a unanimous, en banc Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, including President Obama’s last nominee for the Supreme Court, Judge Merrick Garland, and every other judge on the Circuit appointed by a Democratic president.[15] It is also the position of every other federal appellate court that has considered the issue – six in all. CLC considers this a “radical” position for Mr. Kavanaugh. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in contrast, stated, “[f]ew contested legal questions are answered so consistently by so many courts and judges.”[16] And the Supreme Court’s protection of independent spending by individuals goes back over forty years, to the Court’s 7-1 decision in Buckley v. Valeo, a majority that included Justices William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and Harry Blackmun.

Finally, CLC ends its opening parade of horribles by noting that Judge Kavanaugh has approvingly quoted these words: “restrict[ing] the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.”[17] Those words, in fact, come from the Supreme Court’s 1976 landmark opinion in Buckley v. Valeo, in which seven of the eight justices sitting, including Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall, joined. “Radical” to CLC, perhaps, but mainstream to the Supreme Court. Judge Kavanaugh should quote those Justices approvingly and proudly. CLC is welcome to its view, which it has, as noted, pushed with vigor for many years. That view is that it is consistent with the First Amendment for government to restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others. Let the issue be joined, but let us not suggest that the majority Supreme Court view for over 40 years is somehow “radical.”

CLC then moves to specifics. It first criticizes Judge Kavanaugh’s opinion for the D.C. Circuit in EMILY’s List v. Federal Election Commission.[18] CLC complains, once again, that Kavanaugh, writing for the Court majority, found that only the prevention of corruption justified limits on independent spending in political races by groups such as EMILY’s List, and that equalization was not a valid government objective.[19] We have already covered that ground. And as CLC grudgingly acknowledges, the next year the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission made clear that Kavanaugh got the issue correct.

Later in the report, CLC comes back to EMILY’s List to accuse Judge Kavanaugh of “judicial activism,” “overreach,” and straining to “get the outcomes he wants.”[20] What’s odd is that CLC claims this about a majority opinion, and offers up the fact that one judge on the panel dissented to try to prove that Kavanaugh is the one out of step. Usually, we assume that the judge in dissent is the one who is in overreach mode. (In discussing the case, as it does throughout this report, CLC offers little or no analysis of the arguments actually made in the opinion.) We’re also not sure that Judge Kavanaugh was thrilled about ruling in favor of EMILY’s List, a very liberal group represented by prominent Democratic lawyer Bob Bauer, who would later serve as President Obama’s White House counsel. As Florida State University Law Professor Michael Morley notes, “Emily’s List is a well-reasoned ruling, and a brilliant example of [Judge Kavanaugh’s] willingness to apply constitutional principles neutrally and consistently, regardless of the political affiliation of the litigants before him.”

CLC’s next specific beef is with Judge Kavanaugh’s majority opinion in Independence Institute v. Federal Election Commission.[21] (IFS represented the plaintiffs in Independence Institute). This seems like a strange opinion on which to criticize Kavanaugh’s commitment to democracy, since the question before Kavanaugh’s court revolved around a little used procedural law allowing plaintiffs, in certain situations, to have a three-judge district court, rather than the usual single judge district court, hear the case. The district court judge to whom the case was originally assigned held that a three-judge district court panel was not required in this case. Judge Kavanaugh, writing for the Court of Appeals majority, disagreed. Somehow CLC teases from this ruling on a procedural question that Kavanaugh plans to strike down more laws that CLC thinks are constitutional, and further, that his procedural decision was “novel” and “a departure from precedent,”[22] which, without more information, are curious critiques given that the opinion commanded a majority.

CLC also takes some liberties with the record here. On remand, the district court – now a three-judge panel – ruled against the Independence Institute on the merits. According to the provisions of the same procedural statute, the case then bypassed the Court of Appeals and went straight to the Supreme Court, which affirmed the district court’s decision on the merits. CLC casts this as a “repudiat[ion]” of Judge Kavanaugh’s opinion for the Court of Appeals,[23] but of course it was nothing of the sort – the Supreme Court voiced no opinion on the procedural issue that Judge Kavanaugh had written on for the Court of Appeals majority, because that issue was not even an issue before the High Court. CLC’s description is a blatant misrepresentation not merely of what the Supreme Court held, but even the issue it was asked to address.

At this point, CLC’s report becomes almost schizophrenic. Continuing its section accusing Judge Kavanaugh of “judicial activism,” it cites to Bluman v. Federal Election Commission.[24] Yet in this case, Judge Kavanaugh, writing for a unanimous panel, upheld a federal statute which prohibits non-resident aliens from making contributions or expenditures in federal races. If there was ever a case where a judge harboring the views CLC attributes to Judge Kavanaugh would reach out and strike down a statute to “get the outcome he wants,” Bluman was it. The case was carefully put together with sympathetic plaintiffs, young individuals on long-term but non-immigrant visas, who sought to make only small contributions and expenditures, one on the Republican side, one on the Democratic side, and relying heavily on the opinion in Citizens United to make their case. There was no serious possibility that the plaintiffs – a Canadian and an Israeli, spending very small amounts – were going to corrupt American elections or politicians. Nevertheless, Judge Kavanaugh – note, again, for a unanimous panel – upheld the law’s validity, banning foreign contributions and expenditures in political campaigns.

What seems to upset CLC is that Judge Kavanaugh’s majority opinion interpreted the statute narrowly. That is to say, the plaintiffs were engaging in what, under prior Supreme Court decisions, is called “express advocacy,” speech specifically advocating the election or defeat of a candidate in blunt terms. Judge Kavanaugh, for the Court, interpreted the statute as applying to “express advocacy.” That is, he did not reach out to extend the statute’s application beyond the activity engaged in by the plaintiffs. Remember, the plaintiffs were challenging the constitutionality of the statute, so interpreting the statute broadly would increase the possibility that it might be unconstitutional. The panel appropriately chose not to address constitutional issues not before it. We’re not quite sure how this amounts to “judicial activism” rather than judicial restraint, but then again, we’re not using any cudgel we can find to try to bludgeon Judge Kavanaugh. According to CLC, the decision upholding the foreign national ban leaves doubt as to whether Judge Kavanaugh would support future laws seeking “to strengthen the foreign national ban and … prevent foreign interference in future elections.”[25] We’re generally of the opinion that judges shouldn’t be creating constitutional issues by interpreting statutes to cover behavior not before them and not briefed by the parties. The case tells us only that Judge Kavanaugh and the unanimous panel for which he wrote was unwilling to bring into the case constitutional issues not before them. On appeal to the Supreme Court, Judge Kavanaugh’s opinion for the panel was summarily affirmed.

Finally – still under the section supposed outlining Judge Kavanaugh’s “judicial activism” and his “overreach to get the outcomes he wants” – CLC raises the case of Republican National Committee v. Federal Election Commission.[26] Here, Justice Kavanaugh – a Republican who, according to CLC, harbors “radical deregulatory impulses” – wrote the majority opinion against the Republican National Committee, upholding a campaign finance regulation. CLC notes Kavanaugh’s “adherence to precedent” in the case – an unusual attribute in your typical activist, overreaching judge – but is still upset because Kavanaugh noted that the RNC’s position had “considerable logic and force.”[27] The ruling on the merits was apparently not good enough for CLC, in light of the Judge’s recognition that there are actually arguments on both sides of many constitutional issues. Some people, it seems, just won’t take yes for an answer. CLC worries that merely by upholding the law he has not “signal[ed] his support for the soft money limits on contributions to political parties.” Since they argue that he should be “pressed” on campaign finance issues during his hearing,[28] it sounds as if they want some kind of commitment in advance of how he would rule on a future challenge to the same law, without briefing or specific facts.

Omitted Cases

The campaign finance section of the CLC report ends with RNC v. FEC. But we can’t help but notice that, unlike our review of Kavanaugh’s record (and those of the other potential nominees), CLC ignores certain cases that don’t fit the analysis it seeks to make. For example, there is no mention of Kavanaugh’s votes with the majority in Holmes v. Federal Election Commission or Wagner v. Federal Election Commission.[29] The omission of Wagner is particularly strange, since, at the time it was decided, CLC hailed it as “a major victory for democracy.” But that would not mix well with the argument CLC seeks to make here – that Judge Kavanaugh’s record on democracy is “unsettling” and a threat to democracy – so apparently the Judge’s vote in Wagner had to go down the memory hole.

Voting Rights

The CLC report concludes with two pages reviewing Judge Kavanaugh’s record on voting rights, including the claim that his confirmation may “jeopardize the freedom to vote,”[30] which seems to us a bit overwrought. As this topic takes us out of IFS’s wheelhouse, however, we’ll spare further comment, other than to note that if the lack of accuracy, fairness, or consistency matches that of the analysis of Judge Kavanaugh’s record on campaign finance, it’s not worth much.

Conclusion

We are unlikely ever to see a Supreme Court nominee who is everybody’s first choice, or even favored by all. For the foreseeable future, we can be sure that conservatives will generally be unhappy with the judicial philosophy of Democratic nominees, and liberals will generally be unhappy with the judicial philosophy of Republican nominees. Libertarians may end up in the middle, but there aren’t many true libertarians anyway.

But whatever one thinks of a particular nominee, we ought to be able to discuss that nominee’s record and philosophy fairly and without hysteria. This would be especially true, we think, for an organization that ties its reason for being to the need for truth and integrity in public affairs, and the enhancement of democratic debate.

As we stated at the outset, it is not surprising that CLC would not be happy with a nominee that pleases the Institute for Free Speech (or, indeed, any nominee likely to come from President Trump). But all participants in the debate should be willing and prepared to make their cases honestly and forthrightly, and without alarmism, misrepresentation, and omission.

[1] We did the same in 2017 for the vacancy left by Justice Scalia’s death. See “Make the First Amendment Great Again? Judge Neil Gorsuch’s Views on Free Speech,” Institute for Free Speech. Available at: https://www.ifs.org/make-the-first-amendment-great-again-trumps-potential-supreme-court-nominees-views-on-free-speech/ (2017).

[2] 875 F.3d 1153 (D.C. Cir. 2017).

[3] 793 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2015).

[4] Available at: https://campaignlegal.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/CLC%20Demos%20Kavanaugh%20Brief%207-12-18%209pm.pdf (July 12, 2018).

[5] Demos has made clear it would oppose any Trump nominee. See Adam Lioz, “Power and Fairness at the Supreme Court,” Demos Policy Shop. Available at: http://www.demos.org/blog/6/28/18/power-and-fairness-supreme-court (June 28, 2018).

[6] CLC, supra n. 4, at 1.

[7] Professor Eugene Volokh quotes the entire passage at Eugene Volokh, “Judge Kavanaugh and Prosecutions of Sitting Presidents,” Reason. Available at: https://reason.com/volokh/2018/07/10/judge-kavanaugh-and-prosecutions-of-sitt (July 10, 2018).

[8] CLC, supra n. 4, at 2.

[9] We should note that CLC’s statement notwithstanding, there is not one single standard under which the Supreme Court reviews all restrictions on political speech. Contributions to candidates are reviewed under a different standard than expenditures by candidates or others. See e.g. Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976). Content-related restrictions are reviewed differently from viewpoint-related regulation. See Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 135 S. Ct. 1057 (2015). Many other such distinctions exist. The point here is that all of the justices on the Supreme Court analyze restrictions on campaign contributions and spending as a First Amendment matter, following the criteria set out in Buckley and its progeny.

[10] See e.g. Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976).

[11] See Bradley A. Smith, McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission: An Unlikely Blockbuster, 9 NYU J. L. & Lib. 48, 50-51.

[12] CLC, supra n. 4 at 2.

[13] See Buckley, 424 U.S. 1; McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, 134 S. Ct. 1434 (2014).

[14] CLC, supra n. 4 at 2.

[15] SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, 599 F.3d 686 (2010). The Institute for Free Speech represented plaintiffs SpeechNow.org in that case. The Campaign Legal Center filed an amicus brief in support of the FEC, seeking to uphold the restrictions.

[16] N.Y. Progress & Prot. PAC v. Walsh, 733 F.3d 483, 488 (2d Cir. 2013); see also Republican Party of N.M. v. King, 741 F.3d 1089 (10th Cir. 2013); Texans for Free Enter. v. Tex. Ethics Comm’n, 732 F.3d 535 (5th Cir. 2013); Wis. Right to Life State Political Action Comm. v. Barland, 664 F.3d 139 (7th Cir. 2011); Long Beach Area Chamber of Commerce v. City of Long Beach, 603 F.3d 684 (9th Cir. 2010).

[17] CLC, supra n. 4 at 2.

[18] 581 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2009).

[19] CLC, supra n. 4 at 2-3.

[20] CLC, supra n. 4 at 3-4.

[21] 816 F.3d 113 (D.C. Cir. 2016).

[22] CLC, supra n. 4 at 3-4.

[23] Id. at 4.

[24] 800 F. Supp.2d 281 (D.D.C. 2011). The CLC report incorrectly cites this as a Court of Appeals decision. See CLC, supra n. 4 at fn. 32. Judge Kavanaugh was sitting on the District Court as part of a three-judge panel under the same procedural statute at issue in the Independence Institute case. See supra, text at fns. 21-22.

[25] CLC, supra n. 4 at 4.

[26] 698 F.Supp.2d 150 (D.D.C. 2010).

[27] CLC, supra n. 4 at 5.

[28] Id.

[29] See supra notes 2-3 and accompanying text.

[30] Id. at 6.