NOTE: Please see this blog post for updates on the states that have that have enacted new or improved existing anti-SLAPP laws since the September 15, 2025 update to the publication of our Anti-SLAPP Report Card. Currently 39 states and the District of Columbia have an anti-SLAPP law.

Anti-SLAPP statutes prevent abuse of the legal system by providing additional defenses to those who are sued for exercising their First Amendment rights. The term “SLAPP” is an acronym for strategic lawsuit against public participation.

This report summarizes and evaluates anti-SLAPP statutes in 39 jurisdictions – 38 states and the District of Columbia. (The other 12 states have no functioning anti-SLAPP statute.)

This report begins by explaining the functions of anti-SLAPP statutes. It sketches the structure of a well-designed anti-SLAPP statute; summarizes the changes that have occurred in some state ratings and grades; describes a change in the evaluative language used since the 2023 report was published; explains the importance and operation of the elements of a statute; includes a brief account of the structure and functions of the Uniform Law Commission’s model anti-SLAPP statute (UPEPA); provides a numerical rating and letter grade for each jurisdiction’s statute based on evaluations of how well each statute protects First Amendment rights; and recommends a particular improvement to the statutes of states with poor grades. Because such ratings and grades necessarily involve some judgment and subjectivity, this report explains in detail the rationale of those ratings and grades.

The report also includes an Appendix that provides a plain-English, jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction account of the anti-SLAPP statute in each state and Washington D.C., including both statutory text and some relevant caselaw.

Table of Contents

How Anti-SLAPP Statutes Help Protect Free Speech

The Structure of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

What Has Changed Since the 2023 Report

Policy Choices and Consequences of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

The Uniform Law Commission’s Uniform Public Expression Protection Act

Ratings and Grades of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

How Good Is My Jurisdiction’s Anti-SLAPP Law?

How States With “D” Grades Can Improve

How Anti-SLAPP Statutes Help Protect Free Speech

Anti-SLAPP statutes are designed to address a structural problem within American law: an unscrupulous litigant can use litigation strategically to suppress or punish speech he or she dislikes. Such a litigant would typically claim that the speech constituted defamation and then sue speakers to harass them, silence them, or force them to bear significant litigation costs. Those who encounter such a lawsuit (sometimes called a “SLAPP”[1] or a “SLAPP suit”) are often presented with a harsh choice – accede to the litigant’s demand for settlement (which may include paying compensation, ceasing criticism, and apologizing) or continue to bear heavy legal fees as the suit progresses. We estimate that the median cost of defeating a typical meritless defamation lawsuit in court is $39,000, but mounting such a defense can easily exceed this figure, with legal fees sometimes running into the millions of dollars.[2]

Whether or not the defendant chooses to settle or fight the lawsuit, he or she is likely to suffer substantial losses of speech, reputation, time, and money. These are costs defendants must bear even when faced with lawsuits that plaintiffs have a minimal chance of winning.

Anti-SLAPP statutes attempt to protect speakers from such lawsuits. This report examines statutory protections for those who face these abusive litigation claims, which are typically filed to deter or harass the exercise of First Amendment rights when communicating about matters of public interest. A matter of public interest might include almost any topic – ranging from a governor’s job performance to a restaurant review on Yelp. Generally, policymakers who support anti-SLAPP statutes are attempting to protect the public from retaliatory and groundless lawsuits. Citizens deserve protection when speaking on matters of public concern and, more particularly, they deserve protection against the expenses that strategic lawsuits can force defendants to bear.

Anti-SLAPP statutes are intended to provide a legal defense for those who have been targeted by litigation just because they have said or written something that a plaintiff does not like; the defense of these actions lies in the exercise of one’s First Amendment rights. But anti-SLAPP statutes generally have a procedural aspect that many conventional defenses lack – an opportunity for the defendant to file a motion that forces judicial consideration of certain issues at an early stage in the litigation (known as an anti-SLAPP motion).

Non-lawyers may wish to think of the events triggered by an anti-SLAPP motion as something like a mini-trial. These events will typically require the plaintiff to provide evidence and a relatively focused argument early on. More precisely, this procedural aspect of an anti-SLAPP statute generally forces the plaintiff to demonstrate, at an early stage in litigation, that the case merits consideration in court. Until the plaintiff meets this burden, the defendant generally won’t be subject to discovery (for instance, the defendant won’t have to undergo a deposition or be required to produce documents) or be forced to bear similarly expensive or burdensome aspects of litigation. Without an anti-SLAPP statute, plaintiffs can often strategically impose the significant costs of litigation – in time, money, and aggravation – on defendants.

A good anti-SLAPP statute will impose notable costs on plaintiffs with weak or frivolous cases. If those plaintiffs fail early on to meet the heavier burden of specifying in detail the wrongful conduct they allege, their case will be dismissed. In that circumstance, the fee-shifting provisions of strong anti-SLAPP statutes make plaintiffs liable for reasonable attorney fees and court costs originally borne by the speaker. Such fee-shifting provisions make it more likely that a defendant with limited financial resources who faces a SLAPP will be represented by an attorney. The prospect of fee-shifting encourages attorneys to provide defendants with representation – especially when defendants face weak or frivolous claims.

Strong anti-SLAPP laws encourage potential plaintiffs to think twice before hauling speakers into court with weak or frivolous cases. Plaintiffs must demonstrate that the grounds for the suit lie in actual wrongdoing and not simply in hearing sharply critical statements they dislike and asserting weak or frivolous claims without real evidence. In short, these laws protect defendants who have merely exercised their First Amendment rights. Anti-SLAPP statutes are intended to provide a relatively quick, cheap, and effective way to dispose of one type of meritless lawsuit. Such statutes often enable defendants to achieve rapid dismissal of weak litigation claims, and a good anti-SLAPP law enables defendants to recoup the money they spent on legal costs. Strong anti-SLAPP statutes provide deterrent effects against strategic lawsuits of dubious merit.

Those who seek a more extensive discussion of the rationale for anti-SLAPP laws should read a series of blog posts by attorney and legal commentator Ken White. That series explains in greater detail how anti-SLAPP laws further free speech. White’s first post, “How Do Lawsuits Work Without An Anti-SLAPP Statute, And Why Is That A Problem?”[3] is an excellent explanation of how a SLAPP can threaten free speech. His second post, “How Do Anti-SLAPP Statutes Fix Problems With Civil Litigation And Help Defendants?”[4] is a deeper dive into the mechanisms of anti-SLAPP laws and how they reduce the harm of SLAPPs. He concludes his series with a post titled “What Makes A Good Or Bad Anti-SLAPP Statute?”[5] which, as the title suggests, provides many examples of effective and ineffective state statutes.

The Structure of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

This report surveys 51 jurisdictions (the 50 states and the District of Columbia), finding that 39 of those jurisdictions have functioning anti-SLAPP statutes that were enacted on or before September 15, 2025. The details of those statutes vary, but by and large an anti-SLAPP statute includes or requires these features:

- The scope or coverage of the statute – that is, the nature of the speech it protects – is specified. The statute only protects speech inside the domain of the statute’s protection.

- A defendant – faced with a lawsuit that appears to punish, silence, or deter activities that are based on the exercise of First Amendment rights – has the right to file an anti-SLAPP motion. The motion must argue that the lawsuit’s claim targets expressive conduct that the jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP statute protects. (This report sometimes calls this defendant a “movant”; the movant is the party that files the anti-SLAPP motion.)

- When the anti-SLAPP motion is filed, most or all other aspects of the lawsuit (such as discovery) are suspended until the court makes a final decision on the motion.

- An anti-SLAPP motion typically triggers a two-step process, with the first step borne by the movant and the second step borne by the plaintiff. If the movant satisfies the burden of establishing that the speech is covered by the jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP statute, then the burden of proof shifts to the plaintiff. At this point, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the claim is meritorious – that is, that the claim is well-grounded enough that it might prevail at trial. (This report sometimes calls this plaintiff – when responding to the anti-SLAPP motion – a “respondent.”)

- If the movant prevails on the motion, then the case is dismissed. Under many state laws, the person or entity filing the SLAPP must pay for the speaker’s reasonable legal fees and costs after a SLAPP is dismissed.

- If the respondent prevails on the motion, in some states the movant may immediately appeal the court’s ruling. While the appeal continues, discovery and other aspects of the lawsuit remain suspended. If there is no appeal, then any suspension of the lawsuit ends. If the respondent can establish that the movant filed the motion for improper reasons (for instance, only to create delay), then the movant may be liable for the respondent’s legal fees and costs on the motion in certain circumstances.

The above outline provides an abstract and general portrait of the process created by anti-SLAPP statutes. An examination of anti-SLAPP statutes across jurisdictions will reveal deep similarities, but also significant differences.

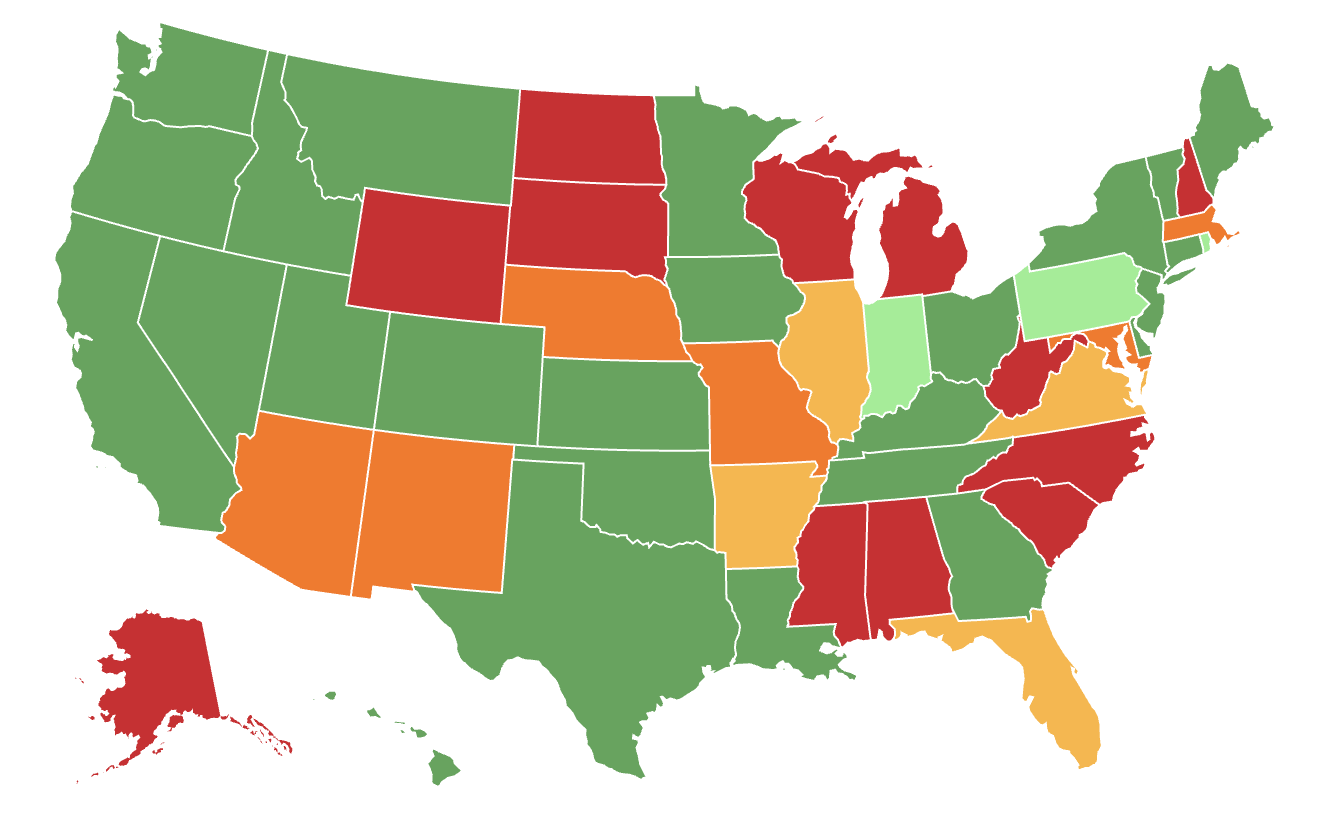

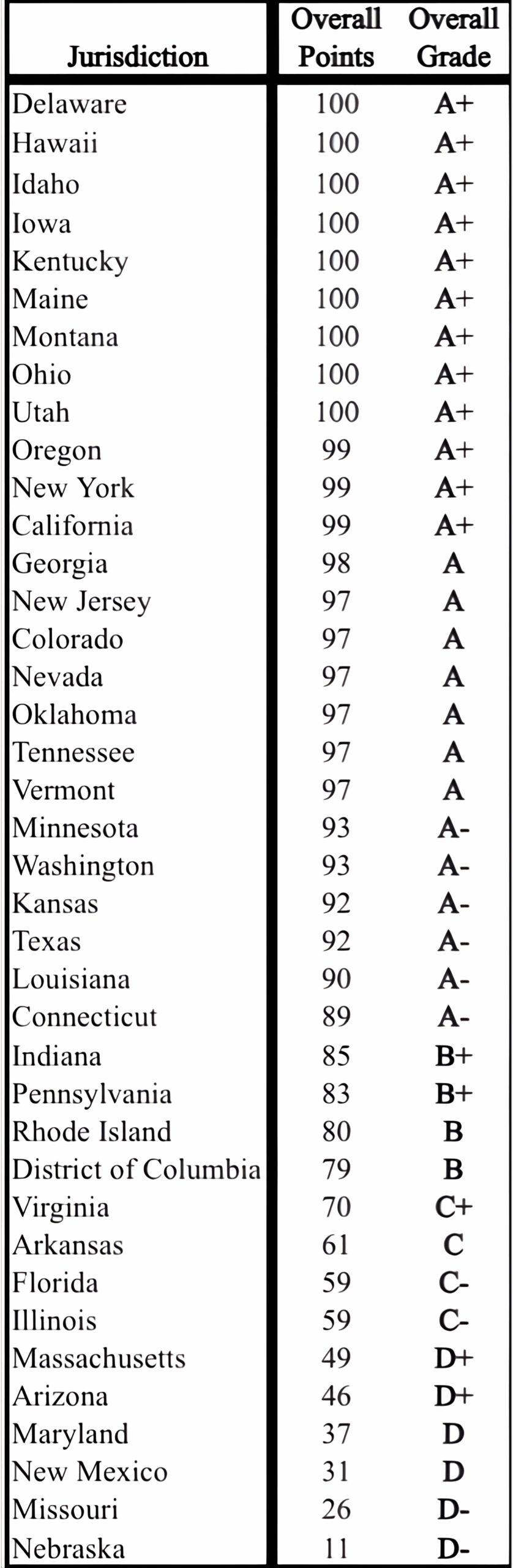

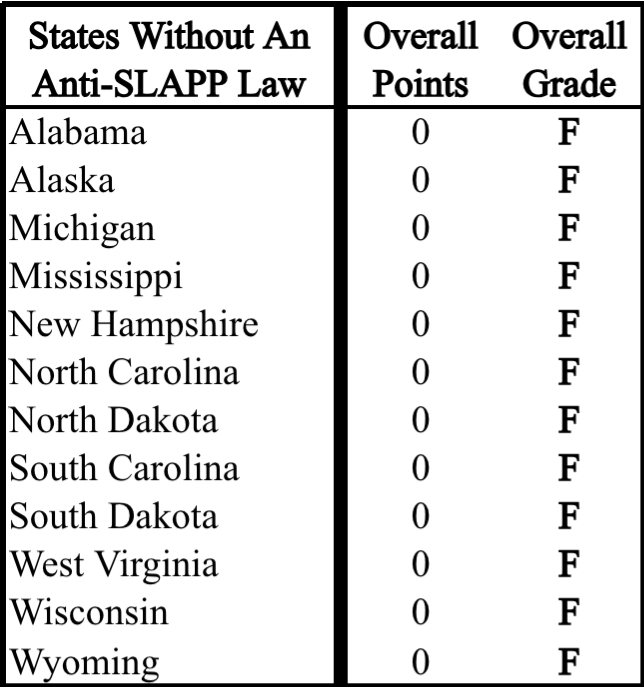

Summary of Results

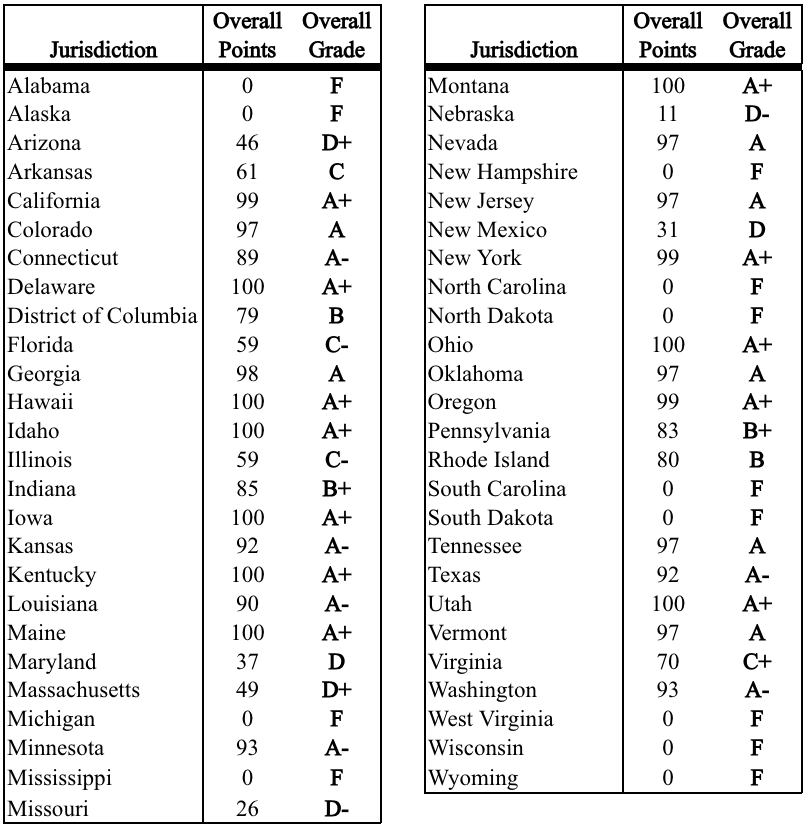

This report finds that there are functioning anti-SLAPP statutes in 39 jurisdictions. It assigns an “A+,” “A,” or “A-” grade to statutes in 25 jurisdictions. The remaining jurisdictions received a grade of “B+” or “B” (four jurisdictions), “C+,” “C,” or “C-” (four jurisdictions), or “D+,” “D,” or “D-” (six jurisdictions). States without an anti-SLAPP statute (twelve) received a grade of “F.”

Rankings of Jurisdictions with Anti-SLAPP Laws

These 12 states with no anti-SLAPP law each received 0 points in the study and an overall grade of “F.”

What Has Changed Since the 2023 Report

The anti-SLAPP landscape has substantially improved since the publication of the 2023 Anti-SLAPP Report, which was based on laws passed prior to September 15, 2023. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia now have a functioning anti-SLAPP statute. Over 56% of the population now resides in a jurisdiction with an excellent anti-SLAPP law, meaning a grade of “A-” or better. Over 62% of the population now lives in a state with a good law, a “B” or better, and 86% is now covered by some form of anti-SLAPP law.

Since the last report, the anti-SLAPP scores assigned to ten states have improved as a result of those states amending existing laws or enacting a new anti-SLAPP law. The score increases in nine of those ten states resulted in a higher grade. Five states that previously had no anti-SLAPP law enacted laws, three states replaced mediocre or weak anti-SLAPP laws with new UPEPA-style statutes, one state attempted to improve its weak anti-SLAPP law with amendments to address its supreme court rulings that weakened the law, and one state’s highest court changed a key procedural rule.

- Delaware: grade increases from a “D-” to an “A+” after enacting the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Florida: the grade remains at a “C-”, although the protections element of the grade has improved from a “D-” to a “D+) after the Florida Supreme Court amended its procedural rules and added the state’s anti-SLAPP statute to the list of rights immediately appealable prior to a final judgment (thereby giving the state 25 points for having a right to interlocutory appeal instead of the previous 0 points).

- Idaho: grade increases from an “F” to an “A+” after enacting the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Illinois: grade increases from a “D+” to a “C-” after enacting a law that modifies the state’s existing anti-SLAPP law to address Illinois Supreme Court rulings.

- Iowa: grade increases from an “F” to an “A+” after enacting an anti-SLAPP statute that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Maine: grade increases from a “C-” to an “A+” after enacting the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Minnesota: grade increases from an “F” to an “A-” after enacting legislation “providing for the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act,” a state law that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Montana: grade increases from an “F” to an “A+” after enacting the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Ohio: grade increases from an “F” to an “A+” after enacting the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act that is modeled after UPEPA.

- Pennsylvania: grade increases from a “D-” to a “B+” after enacting a statute closely modeled after UPEPA.

Additionally, some of the headings and portions of the report’s narrative have changed. As explained in detail below, the report analyzes each state’s law in two key categories, the most important being the scope of speech protected by the statute. The other category describes features of the law that can be used by speakers to protect their rights. Since not all of these features of anti-SLAPP laws are procedural, we now refer to the different “protections” that statutes provide.

Recent Trends Show Strong Improvements Nationally

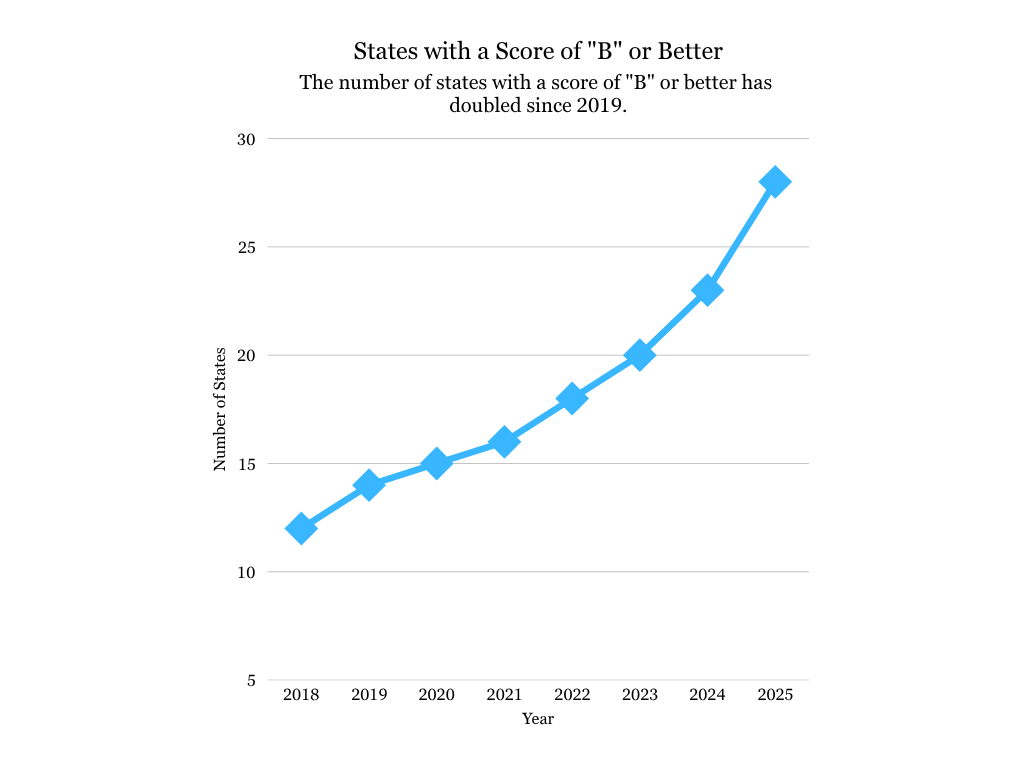

The improvements reflected in the 2025 scorecard continue the recent trend of increasing state legislative and judicial awareness of the importance of anti-SLAPP laws to free expression. Along with the eight good or excellent new or substantially improved state anti-SLAPP laws in this scorecard, eight more excellent laws were adopted between 2019 and 2023. These were Colorado[6] and Tennessee (2019); New York (2020); Washington (2021); Hawaii and Kentucky (2022); and New Jersey and Utah (2023).

These followed the enactment of other “A” grade laws by Nevada (2013), Oklahoma (2014), Georgia (2016), Kansas (2016), and Connecticut (2017).

- The number of states with “B” grade or better laws in 2018 was just 12; in 2025, there are now 28 such states. That represents a 133% increase.

- In 2018, the portion of population covered by good laws was just 33.6%. Today, it’s 62.9%. That is an 87% increase.

- Today, 86.2% of the population lives in a state with an anti-SLAPP law, another record high.

On July 15, 2020, the Uniform Law Commission adopted its model anti-SLAPP law, which has already led to excellent new or revised laws in ten states. Indeed, only three of the good anti-SLAPP laws (ones that receive a “B” grade or higher) were on the books at the beginning of the 21st century (Rhode Island, Indiana, and Louisiana)[7]. And of the other 29 “B” grade or better laws, 21 (72%) have been enacted since 2010.

Methodology Updates

No changes in methodology have been made since the last report.

Policy Choices and Consequences of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

This report evaluates the details of anti-SLAPP statutes and assigns the highest value to the anti-SLAPP statutes that best protect First Amendment rights. Understanding the operation of any particular anti-SLAPP statute requires a focus on the policy choices and consequences entailed by the text of that statute. The machinery of those policy choices and consequences is discussed immediately below. More details on each jurisdiction’s statute are available in the Appendix.

- What conduct does the anti-SLAPP statute cover and protect? The scope of the most speech-protective anti-SLAPP statutes is extensive. The strongest anti-SLAPP statutes, like those in California and Tennessee, and the Uniform Law Commission’s Model Act (discussed in the next section), protect broad sectors of speech made in any forum and on any matter of public concern. Yet the coverage of some other anti-SLAPP statutes is narrow. Some anti-SLAPP statutes – New Mexico’s is one example – only protect speech that is directly addressed to a government body. As discussed below, a few anti-SLAPP statutes protect speech only about a narrow issue or in a particular forum.

This report assigns the greatest number of points to anti-SLAPP statutes that protect speech on any matter of public concern in any forum.

- Is discovery permitted once an anti-SLAPP motion is filed? In some jurisdictions, like Washington, the filing of an anti-SLAPP motion suspends all other litigation proceedings (for example, discovery proceedings) until the motion is resolved. In other jurisdictions, however, discovery after the filing of an anti-SLAPP motion is at the discretion of the court. California is an example of such a state. In these states, the court decides whether to allow continued discovery, typically requiring the plaintiff to produce a motion showing “good cause” for discovery. In that circumstance, the court will typically narrow or limit the scope of permitted discovery. A few jurisdictions – Nevada and the District of Columbia are two examples – supply other tests for judicially permitted discovery; for instance, discovery may be permitted if it is necessary to meet the party’s burden of proof. Indiana’s statute suspends all discovery, except for discovery related to the anti-SLAPP motion.

This report assigns the most points to anti-SLAPP statutes that completely suspend discovery and all other proceedings upon the filing of the anti-SLAPP motion.

- What must the plaintiff show to defeat an anti-SLAPP motion? The standard of proof that a respondent must satisfy to defeat an anti-SLAPP motion (alluded to in part D of the “The Structure of Anti-SLAPP Statutes” section) varies widely among jurisdictions. In several states, the respondent must show that there is a probability that he or she will prevail at trial. For example, the California and Georgia statutes operate this way. As a practical matter, this requirement is often understood as constituting a burden to demonstrate an initially plausible case. In Massachusetts, for example, a respondent must show that the movant’s actions both caused actual injury to the plaintiff and that those actions were without reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law. In Illinois, the respondent must provide clear and convincing evidence that the state’s anti-SLAPP law does not immunize the defendant from liability. The requirements imposed on the plaintiff in a few other jurisdictions are difficult to sum up, but all are described in the Appendix.

This report assigns the greatest number of points to anti-SLAPP statutes that come closest to the Uniform Law Commission Model Act, especially its requirement that a plaintiff “establish a prima facie case as to each essential element” of the lawsuit.

- Is there a right of interlocutory appeal? If an anti-SLAPP motion is denied, several states, like Nevada and New Mexico, grant the movant a statutory right to interlocutory appeal of that ruling. In that event, the case remains suspended until the anti-SLAPP motion is ultimately resolved. An “interlocutory” appeal, speaking generally, is a request to a higher court for it to decide a particular issue immediately. In most litigation, interlocutory appeals are difficult to obtain, so this right of appeal is an important feature of an anti-SLAPP law. Without it, a defendant who loses an anti-SLAPP motion would be forced to continue to litigate the entire trial before the finding on the motion could ever be appealed.

An interlocutory appeal on an anti-SLAPP motion suspends other aspects of the litigation until a higher court can rule on the anti-SLAPP motion. However, most states do not expressly provide for such a right of appeal. Some states, such as New Mexico, also allow for appeal if the court fails to rule on the anti-SLAPP motion after a given period. This policy choice avoids leaving the anti-SLAPP litigant under the specter of litigation if the court fails to act with reasonable speed on an anti-SLAPP motion.

As attorney Ken White has explained, the provision of a right of interlocutory appeal creates a strong protection for First Amendment liberties, especially because it blunts the force of lawsuits that target speech.[8]

This report assigns the most points to anti-SLAPP statutes that provide for an immediate right of appeal if a lower court denies an anti-SLAPP motion.

- Can the defendant recover costs and attorney fees from the plaintiff? Many states provide for the mandatory award of attorney fees and costs if the defendant prevails on an anti-SLAPP motion. Statutes in California and Tennessee, among others, have this provision. Other states, like Nebraska, allow the court to decide whether to award attorney fees and costs, and one state (Maryland) makes no provision for fee- and cost-shifting at all. Some states that shift fees and costs provide that they may be shifted only to benefit the prevailing movant and not the prevailing respondent; the states that allow fee-shifting to benefit the respondent typically require a showing that the anti-SLAPP motion was frivolous or that it was filed solely with the intent to delay resolution of the action. Others, such as Pennsylvania and Ohio, base fee shifting on immunity from such lawsuits or liability.

This report assigns the most points to anti-SLAPP statutes that require an award of attorney fees and costs to defendants who win an anti-SLAPP motion or otherwise prevail against a SLAPP.

- Does the statute instruct courts to interpret it broadly or liberally? A few anti-SLAPP statutes instruct courts to interpret the anti-SLAPP statute “broadly” (see, for example, California’s statute) or “liberally” (see Oregon’s statute). Sometimes, a judge might find it unclear whether some particular instance of First Amendment-related speech or conduct should fall within the protections granted by an anti-SLAPP statute. Generally, language that commands broad or liberal interpretation might increase the likelihood of the application of an anti-SLAPP statute by interpretively giving that speech or conduct the benefit of the doubt. On the other hand, anti-SLAPP statutes that lack instructions for broad or liberal interpretation might face an increased likelihood that a court would, in practice, narrow their scope; for example, by requiring more exacting tests for an anti-SLAPP motion’s success than those in the statute. Missouri is one state where its anti-SLAPP statute has been interpreted through case law due to a lack of instruction about judicial interpretation.

This report assigns the most points to anti-SLAPP statutes that expressly encourage courts to read the statutory language expansively to protect free speech.

The Appendix describes each jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP statute within its scope; sometimes, these summaries include notes about the interaction of relevant caselaw with the statute’s operations.

The Uniform Law Commission’s Uniform Public Expression Protection Act

In 2020, the Uniform Law Commission (ULC),[9] a nonprofit and nonpartisan organization of state commissioners on uniform laws that recommends and drafts model state legislation, produced its Uniform Public Expression Protection Act (UPEPA).[10] UPEPA is a model anti-SLAPP statute.

When evaluated using the criteria as described in the next section, UPEPA contains provisions that are superior to almost every current state anti-SLAPP statute (at least from the perspective of First Amendment protections). In particular, UPEPA:

- Applies to and protects not only communication directed to government or that pertains to government proceedings, but also to the exercise of First Amendment rights on matters of public concern in any forum (see Section 2 of UPEPA).

- Provides for a general stay of proceedings between the movant and respondent upon the filing of a special motion for expedited relief; that motion provides for a stay of all related proceedings, including discovery and pending hearings (see Section 4 of UPEPA).

- Creates an obligation for the plaintiff (the respondent in the anti-SLAPP motion) to establish a prima facie case for each essential element of the lawsuit (see Section 7 of UPEPA).

- Establishes that the movant may appeal as a matter of right if a court denies the anti-SLAPP motion (see Section 9 of UPEPA).

- Requires the court to award costs and reasonable attorney fees and expenses to the prevailing movant. It awards costs and fees to the prevailing respondent, but only if the motion was frivolous or filed solely to delay the litigation (see Section 10 of UPEPA). A voluntary dismissal of the lawsuit by the respondent establishes that the movant prevailed.

- Commands the court that interprets the Act to apply and construe it broadly to protect First Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution and under similar free expression rights of state constitutions (see Section 11 of UPEPA).

In short, policymakers who seek to improve their own jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP statute are well-advised to consider the Model Act as proposed by the Uniform Law Commission. The Model Act contains protections for free speech that are more extensive than any existing statute. Furthermore, if the relevant text of the Model Act were amended into a state’s anti-SLAPP statute, federal courts would be more likely to incorporate those provisions into their deliberations than is the case with most states’ anti-SLAPP statutes.

Ratings and Grades of Anti-SLAPP Statutes

Of the 51 jurisdictions examined in this report, 39 currently have functioning anti-SLAPP statutes. Twelve states do not have a functioning anti-SLAPP statute. This report’s evaluative method is based on quantitative assessments that cover two broad categories. First, and most importantly, what is the scope of speech covered by each jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP law? Second, how comprehensive are the protections for speakers that are included in or required by each jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP law? Ultimately, this report compiles quantitative assessments to produce one overall grade for each jurisdiction’s statute. Statutes that best protect the First Amendment rights of litigants received the highest scores and grades.

The report considers caselaw that interprets the statute if the caselaw appears to have changed the operation of the statute. In some cases, such interpretations limit the protections available to defendants. In others, courts interpret the law to provide more protection for speech. As such, each jurisdiction’s scores and grades reflect how the law is applied in court. If judicial interpretations result in the narrowing of free speech protections in a manner that is contrary to the intent of state lawmakers, then lawmakers should modify the law to clarify the legislature’s intent. This report considers caselaw through May 31, 2025.

Overall Grades

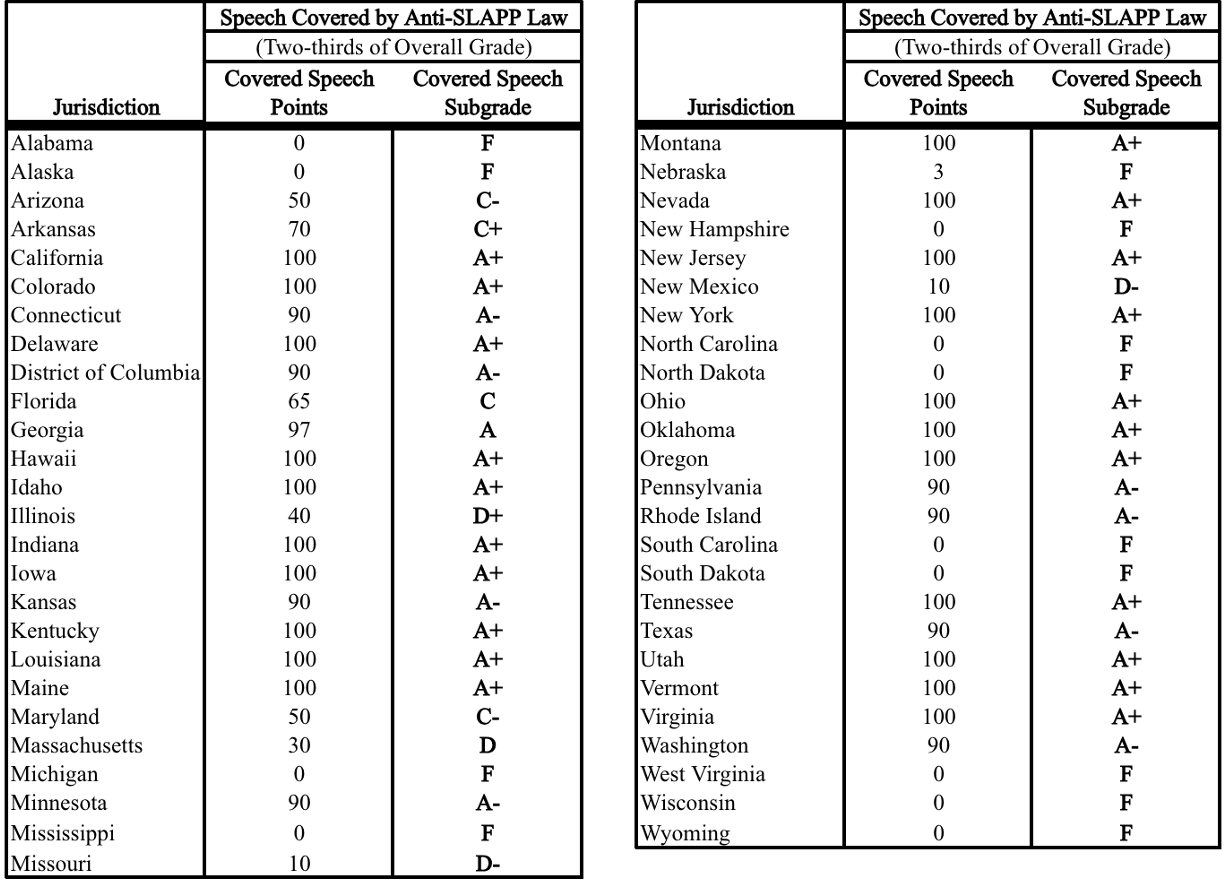

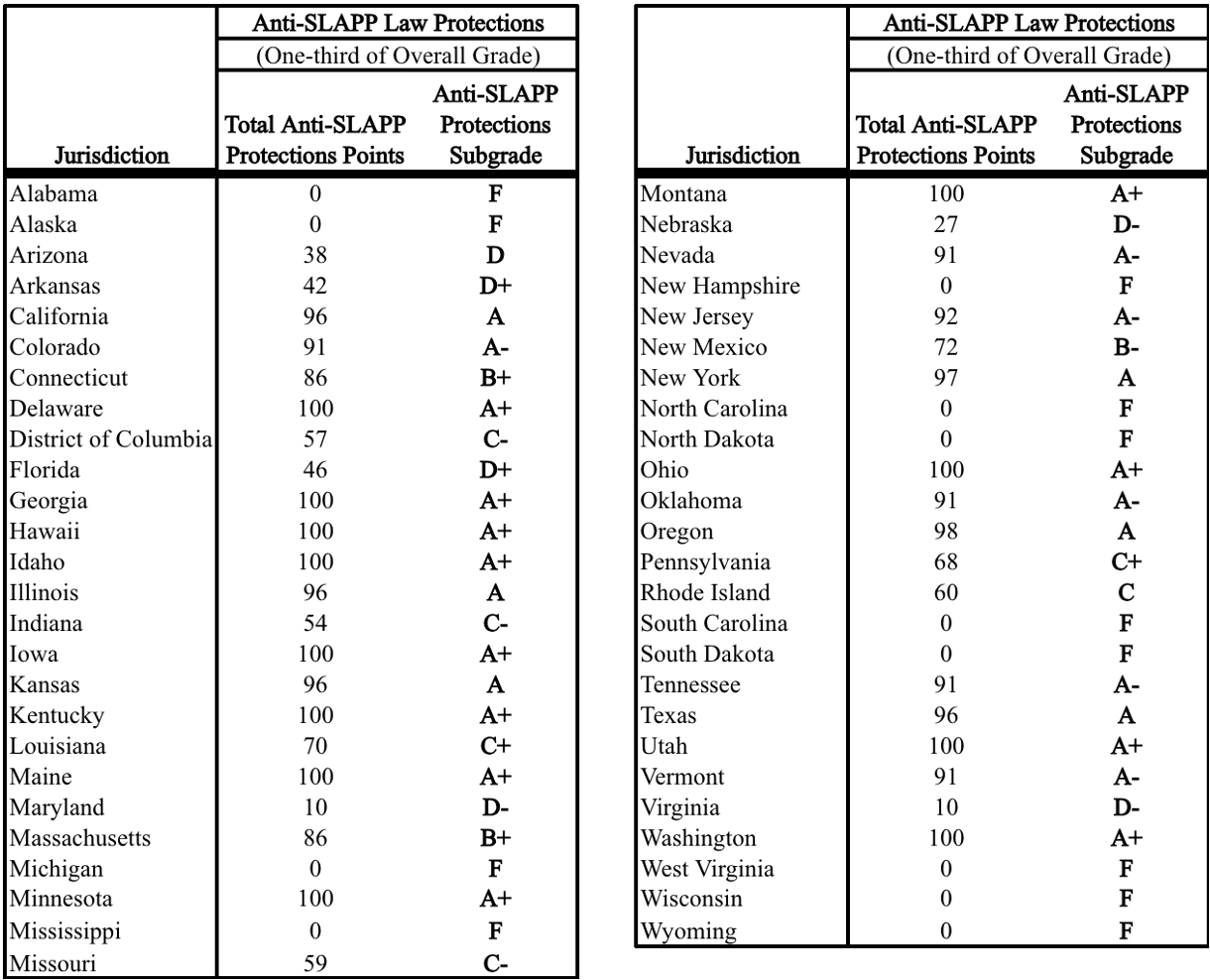

This report assigns an overall grade to each state’s anti-SLAPP law. Two-thirds of the overall grade is based on the scope of speech that the statute covers; one-third of the overall grade is based on the other features of the law that provide protections for speakers. This report assigns a relatively large weight (a two-thirds share) to the scope of the statute’s coverage because other provisions containing strong protections for speech are of no help to a speaker if the scope of the statute excludes the speech at issue. States with no anti-SLAPP law are assigned a grade of “F.”

Each grade was calculated by adjusting and summing the subscores described below. More precisely, each grade was calculated by multiplying the subscore for the scope of speech that the statute protects by two-thirds; then multiplying the sum of the subscores for the protections for speakers in the statute by one-third; then summing the two resultant products to produce an overall score. For example, consider Indiana. Its subscore for the scope of speech is 100 while the state’s total subscores for the protections for speakers is 54. Two-thirds of 100 is 66.67, and one-third of 54 is 17. The sum of 66.67 and 17 is 85, Indiana’s overall score. The jurisdiction’s overall grade is simply a function of its overall score.[11]

Scoring Rubric Summary

This report evaluates six aspects of anti-SLAPP statutes in the 39 jurisdictions described above.

The subscore that measures the scope of protected speech ranges from 0 to 100; a perfect subscore is assigned to measures that protect the broadest range of speech – any speech on a matter of public concern in any forum.

The other five subscores evaluate the effectiveness of each component of a law with regard to protecting First Amendment rights. The maximum subscore for each of those five protections ranges from 3 to 40; the minimum subscore for each is 0. If a state’s anti-SLAPP law providesthe highest First Amendment protections for each of the five aspects, it receives a perfect subscore of 100 on this portion of the evaluation.

The criteria for the six subscores follow. Although the criteria for each are briefly described below, the statutory details are explained in the jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction accounts in the Appendix.

Each of these subscores is based on how closely the state’s statute corresponds with the underlying policy of the model anti-SLAPP law (UPEPA) recommended by the Uniform Law Commission. The UPEPA model provides a vigorous set of protections for First Amendment rights.

The report also provides two sets of subgrades that derive from these subscores. The resulting two subgrades should not be confused with the overall grade ultimately assigned to each statute. Each subgrade evaluates only one portion of one statute. Said differently, these subscores and subgrades are something like the interim evaluations that students receive when taking a class; ultimately, all the subscores and subgrades are compiled to produce an overall score and an overall grade.

The interpretation and evaluation of statutes is far from an exact science. The evaluative choices that this report contains are transparent; a reader who objects to the quantitative or interpretive significance this report assigns to any aspect of the anti-SLAPP landscape can use any part of the data or methodology to produce and calculate a different set of evaluations.

The Scope of Protected Speech (Maximum Subscore: 100)

The ULC Model Act protects a wide spectrum of speech and expressive conduct, as follows:

[T]his [act] applies to a [cause of action] asserted in a civil action against a person based on the person’s:

- communication in a legislative, executive, judicial, administrative, or other governmental proceeding;

- communication on an issue under consideration or review in a legislative, executive, judicial, administrative, or other governmental proceeding; or

- exercise of the right of freedom of speech or of the press, the right to assemble or petition, or the right of association, guaranteed by the United States Constitution or [cite to the state’s constitution], on a matter of public concern.

Some anti-SLAPP statutes are designed to protect all speech on matters of public concern while other anti-SLAPP statutes have a more limited scope. For instance, some anti-SLAPP statutes are limited to the protection of speech related to matters that a government body is considering or reviewing. Other anti-SLAPP statutes are limited to the protection of speech expressed during a government meeting or directly to a government body. A few anti-SLAPP statutes have an even more sharply limited domain.

Statutes with a broad scope of coverage – those which specify that they protect all speech related to a “matter of public concern,” “public issue,” or an “issue of public interest” – received the maximum subscore of 100 points in this category.

However, the scope of coverage of some anti-SLAPP statutes is smaller.

- Because Georgia courts sometimes read its anti-SLAPP statute narrowly (despite the statute’s internal instruction that it should be read broadly), that statute received a subscore of 97 in this category.

- Because several statutes contain narrow content-related exemptions from their broad protections, those statutes each received a subscore of 90 points.

- The Arkansas statute appears to provide broad coverage for speech, but a more restrictive judicial interpretation is possible. To date, there is no caselaw on the scope of speech protected by the law. Thus, the statute received a subscore of 70 points.

- Because Florida’s statute protects both statements made before a governmental entity and statements made in connection with created texts, such as books, plays, news articles, and movies, that statute received a subscore of 65.

- Maryland’s brief and unusually worded law also limits the amount of speech potentially covered. It defines a SLAPP suit in part as one that is “[b]rought in bad faith” and “[i]ntended to inhibit or inhibits the exercise of rights under the First Amendment.” In effect, this standard narrows the scope of speech protected by the law. As a result, the law received a subscore of 50 points.

- Arizona’s statute, as revised in 2022, now covers all constitutionally protected speech on matters of public concern. Unfortunately, it also has an odd provision not in any other anti-SLAPP statute. It requires that a defendant filing an anti-SLAPP motion must show that the lawsuit “was substantially motivated by a desire to deter, retaliate against or prevent the lawful exercise of a constitutional right.” Plaintiffs suing speakers will not be required to respond to an anti-SLAPP motion until or unless the target of their lawsuit has established this “prima facie proof.” Because of this uncertainty about how the courts will interpret this provision and the unique burden of proof placed on a speaker, this law received a subscore of 50.

- The Massachusetts statute generally confines its reach to matters involving government action but also includes speech that is “reasonably likely” to encourage government consideration or review. Consequently, the Massachusetts statute receives a subscore of 30.

- The Illinois statute appears limited because it provides an exception to the speech covered when the speech is “not genuinely aimed at procuring favorable government action, result, or outcome.” The law was amended in 2025 to address state Supreme Court rulings that narrowed the reach of the original law. However, it’s far from clear how the state’s Supreme Court will interpret the amended law and the previous exception. Due to this uncertainty in the coverage of the law, it receives a subscore of 40 points.

- Missouri and New Mexico’s statutes only protect “conduct or speech undertaken or made in connection with a public hearing or public meeting;” those statutes received a subscore of 10.

- Nebraska’s anti-SLAPP law only protects speech in an even narrower domain. It only applies to speech by public applicants, permittees, and those materially connected to the entitlement at issue. That statute received a subscore of 3.

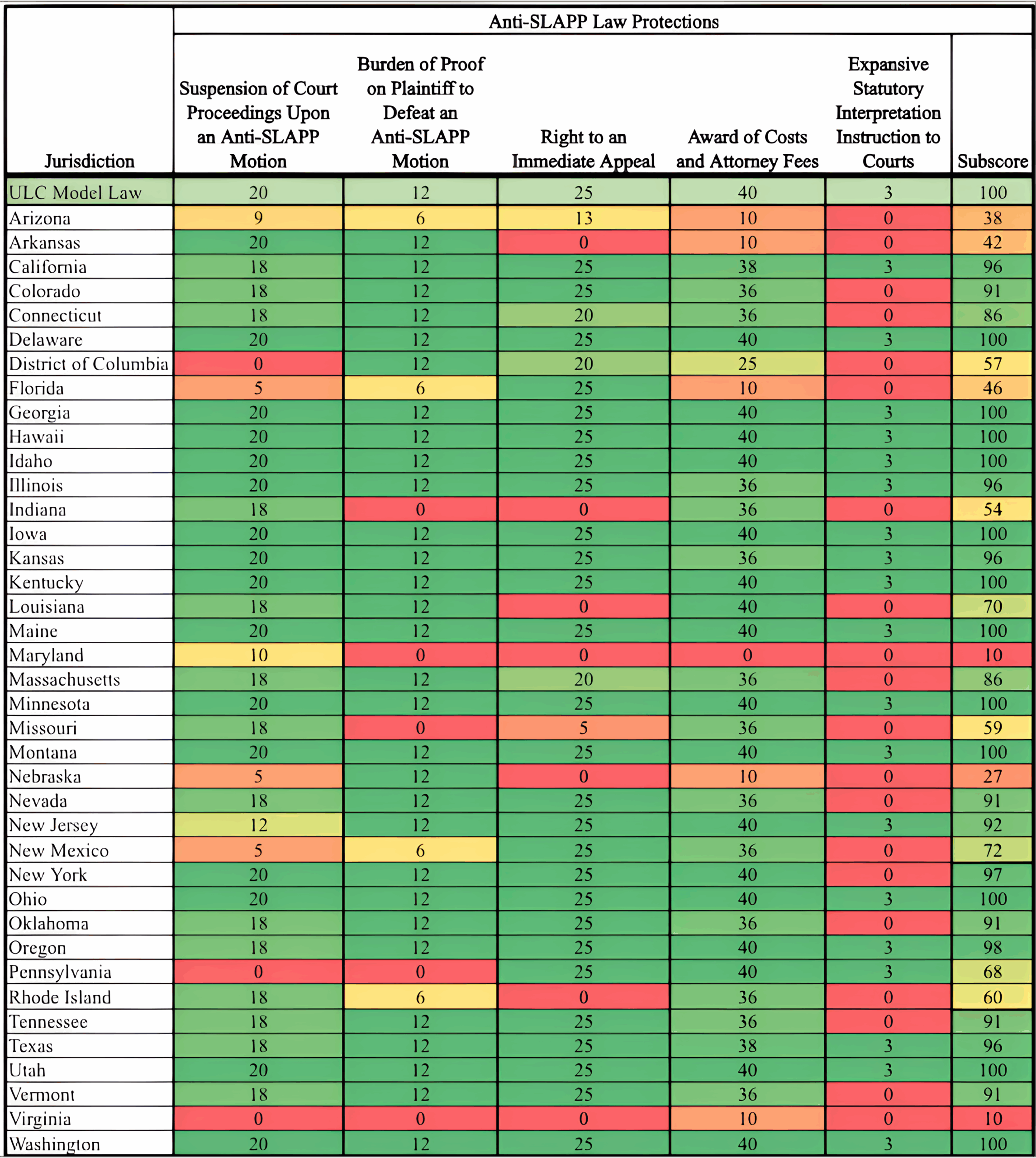

Other Anti-SLAPP Law Protections (Maximum Sum of Five Subscores: 100)

These five subscores measure various features to protect First Amendment rights that are contained in or implied by anti-SLAPP statutes.

1. Suspension of Court Proceedings Upon Anti-SLAPP Filing (Maximum Subscore: 20). The ULC’s UPEPA and several state statutes suspend all proceedings when an anti-SLAPP motion is filed; the statutes of many other jurisdictions with anti-SLAPP statutes suspend discovery once an anti-SLAPP motion is filed. If a jurisdiction’s statute provides for a stay of all proceedings, it receives a subscore of 20 points.

- Statutes that only stay discovery, but not other proceedings, received a subscore of 18 points.

- A few statutes do not suspend proceedings or discovery, but they might limit discovery by requiring the court to schedule an expedited anti-SLAPP hearing upon the filing of such a motion; those statutes received subscores of 5.

- New Jersey’s statute creates “a presumption that such a stay [of proceedings] shall be granted;” its statute received a subscore of 12.

- Maryland’s statute allows the target of a SLAPP suit to file various motions that will impede discovery, but it is unclear from the statute whether the court must grant them; its statute received a subscore of 10.

- Finally, the statutes of those jurisdictions that neither make provisions for suspension of discovery nor for an expedited hearing in the event of the filing of an anti-SLAPP motion received subscores of 0.

2. The Burden of Proof Required to Defeat an Anti-SLAPP Motion (Maximum Subscore: 12). If a relevant anti-SLAPP motion is filed, the ULC model requires that the motion succeed if either:

- the responding party fails to establish a prima facie case as to each essential element of the [cause of action]; or

- the moving party establishes that:

- the responding party failed to state a [cause of action] upon which relief can be granted; or

- there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on the [cause of action] or part of the [cause of action].

The ULC model and the statutes of many jurisdictions with strong anti-SLAPP laws impose a burden of proof on the plaintiff. In particular, the plaintiff must show the court that the original lawsuit was meritorious. The statutes of these jurisdictions received subscores of 12 points – the maximum subscore for this category.

- The statutes of a few states require or imply a response to an anti-SLAPP motion from the respondent, but do not appear to shift the burden of proof to the respondent during the motion’s disposition. These statutes received subscores of 6 points.

Five states place a relatively heavy burden of proof on the movant but appear to create no burden of proof for the respondent; these statutes received a subscore of 0.

3. The Right of Immediate (“Interlocutory”) Appeal (Maximum Subscore: 25). An interlocutory appeal, speaking generally, is a request to a higher court to decide a particular issue immediately; such interlocutory appeals suspend other aspects of the litigation until the outcome of that particular issue is determined. The statutes of several states prioritize the decision of whether a lawsuit is appropriately disposed of with an anti-SLAPP motion by providing for interlocutory appeal of this question upon a trial court’s disposition of the motion. Statutes that provide for an immediate right of appeal received the maximum subscore of 25 points in this category. If the state’s highest appellate court interprets the statute as providing for an interlocutory appeal, the state receives a subscore of 20 points. If there is no right to an interlocutory appeal, the statute receives a subscore of 0.

- Arizona has a right to an interlocutory appeal, but it is conditioned on the defendant establishing the lawsuit was “substantially motivated by a desire to deter, retaliate against or prevent the lawful exercise of a constitutional right.” Its statute received a subscore of 13.

- Although Missouri’s statute appears to provide for rights of interlocutory appeal, its caselaw suggests that a court’s denial of an anti-SLAPP motion cannot, itself, be appealed;[12] its statute, therefore, received a subscore of 5.

4. Award of Costs and Attorney Fees (Maximum Subscore: 40). The ULC Model Act and many jurisdictions’ anti-SLAPP statutes provide for the mandatory award of costs and attorney fees to the successful anti-SLAPP movant. Such awards will appropriately deter SLAPP-related misbehavior. Statutes of jurisdictions that require this kind of cost- and fee-shifting received subscores of 40 points in this category. Some state statutes with mandatory fee-shifting do not recognize a voluntary dismissal of the lawsuit by the respondent as establishing that the movant prevailed. These states receive a subscore of 36. If the state’s highest appellate court interprets the statute so that a voluntary dismissal of the lawsuit by the respondent establishes that the movant prevailed, the state receives 38 points.

- Oklahoma’s statute mandates the payment of “attorney fees and other expenses” to movants “as justice and equity may require.” To date, the state’s courts have interpreted fee-shifting as mandatory; as a result, this clause appears to have little force. Therefore, Oklahoma’s statute received a subscore of 38 points.[13]

- Since District of Columbia courts have said that the jurisdiction’s law provides a presumption to award fees, that law received a subscore of 25.

- Florida has an unusual “loser pays” rule on an anti-SLAPP motion; its statute received a subscore of 10, as this rule greatly discourages the use of an anti-SLAPP motion.

- Other jurisdictions assign the court the option, not the requirement, of cost- and fee-shifting in this circumstance; the statutes of those jurisdictions received subscores of 10.

- Other jurisdictions have no provision for cost- and fee-shifting; the statutes of those jurisdictions received subscores of 0.

5. Expansive Statutory Interpretation Instruction (Maximum Subscore: 3). The ULC model and several jurisdictions’ anti-SLAPP statutes provide guidance about interpretation of their own language: they instruct judges to read the anti-SLAPP statute itself “broadly” or “liberally.” Statutes that contain this kind of interpretive instruction received subscores of 3 points in this category; statutes without such an instruction received subscores of 0.

How Good Is My Jurisdiction’s Anti-SLAPP Law?

As explained above, this report assigns an overall grade to each jurisdiction’s anti-SLAPP statute. Two-thirds of the overall grade is based on the scope of speech the statute covers; one-third of the overall grade is based on the other features of the law that provide protections for speakers in each state’s law. States with no anti-SLAPP statute are assigned a grade of “F.” The table contains the same overall grades and scores for the states as in the Summary of Results section, but the states are arranged in alphabetical rather than ranking order.

How Much Speech Is Protected? (Maximum Subscore: 100)

As explained above, two-thirds of the overall grade is based on the scope of speech that the statute covers. That’s because other features that provide strong statutory protections are of no help to a speaker if the scope of the statute excludes the speech at issue.

Statutes with a broad scope of coverage – those that protect all speech related to a “matter of public concern,” a “public issue,” or an “issue of public interest” – received the maximum subscore of 100 points in this category.

Here’s how each jurisdiction scores on this portion of the evaluation.

Other Anti-SLAPP Law Protections (Maximum Sum of Five Subscores: 100)

As noted earlier, one-third of each statute’s overall grade is based on how well the other components of each state’s law safeguard First Amendment rights. For each jurisdiction, these five other protection subscores are summed together to produce one rating.

The criteria and maxima for these five subscores follow. (See the Policy Choices and Consequences of Anti-SLAPP Statutes section for more information on these provisions.)

- Suspension of Court Proceedings Upon an Anti-SLAPP Motion (20 points)

- Burden of Proof on Plaintiff to Defeat an Anti-SLAPP Motion (12 points)

- Right to an Immediate (Interlocutory) Appeal (25 points)

- Award of Costs and Attorney Fees (40 points)

- Expansive Statutory Interpretation Instruction to Courts (3 points)

Here is a summary of each jurisdiction’s subscores and subgrades for these five protective features found in a robust anti-SLAPP law.

Here is a summary of the points earned for these five protective components in each jurisdiction with an anti-SLAPP law:

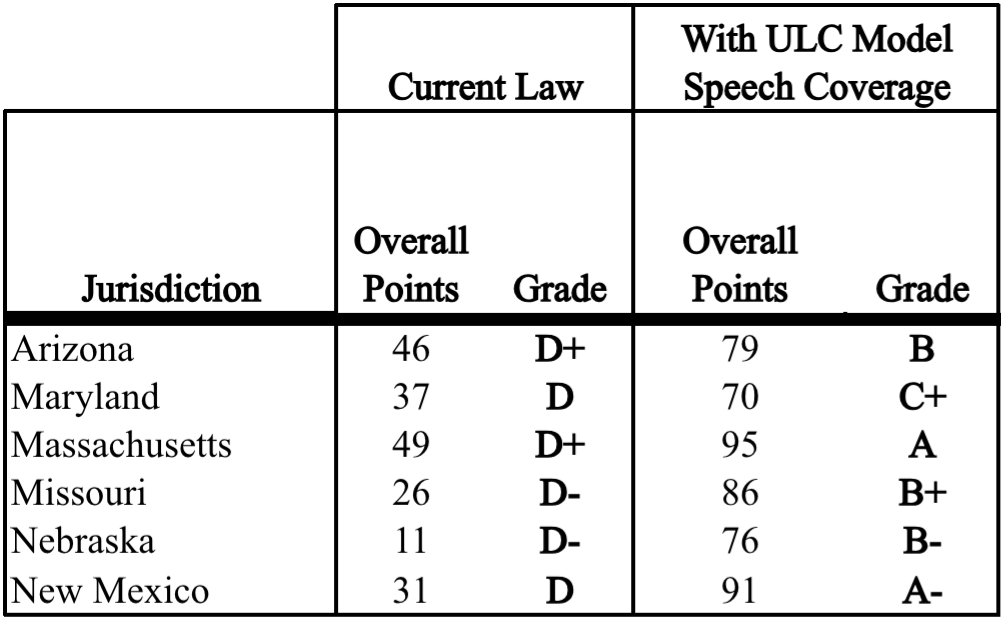

How States With “D” Grades Can Improve

Most of the states with “D” grades have a fundamental flaw in their anti-SLAPP statutes—the scope of the statute covers too little speech. All six states with “D” grades could improve their grades to “B-” or better simply by expanding the scope of their statutes to cover the same kinds of speech recommended by the Uniform Law Commission’s Model Act. (In short, the Uniform Law Commission’s model law protects any speech about a matter of public importance in any forum. The model is explained in a previous section.)

Three of those six states would reach “B+” or better, including two “A” or “A-” grades. Every state would achieve at least a “C+” by adopting the ULC model for the scope of speech covered.

If States With “D” Grades Adopted the ULC Model on Speech Covered by the Law, Here’s How Their Grades Would Rise

- Penelope Canan and George W. Pring, two professors (Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of Central Florida, and Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, respectively), are typically credited with coining the term. See generally their article, “Studying Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation: Mixing Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches,” Law and Society Review, vol. 22 (1988): 385. Over time, the conventional understanding of a SLAPP has expanded: the concept’s originators initially viewed the subject matter of a SLAPP as necessarily involving communications to a government body about a government action, but the modern understanding of a SLAPP is not limited in this way. ↩︎

- David Keating, “Estimating the Cost of Fighting a SLAPP in a State With No Anti-SLAPP Law,” Institute for Free Speech Blog (June 16, 2022), https://www.ifs.org/blog/estimating-the-cost-of-fighting-a-slapp-in-a-state-with-no-anti-slapp-law/. For more on the methodology used to arrive at such figures, see Paula Hannaford-Agor and Nicole L. Waters, “Estimating the Cost of Civil Litigation,” National Center for State Courts (January 2013), https://perma.cc/43VC-SSGZ ↩︎

- Ken White, “What Is An Anti-SLAPP, Anyway? A Lawsplainer Series – Chapter One: How Do Lawsuits Work Without An Anti-SLAPP Statute, And Why Is That A Problem?,” The Popehat Report (October 26, 2020), https://perma.cc/EE6F-7TT7. ↩︎

- Ken White, “What Is An Anti-SLAPP, Anyway? A Lawsplainer Series – Chapter Two: How Do Anti-SLAPP Statutes Fix Problems With Civil Litigation And Help Defendants?,” The Popehat Report (October 29, 2020), https://perma.cc/LKR2-KS8D. ↩︎

- Ken White, “What Is An Anti-SLAPP, Anyway? A Lawsplainer Series – Chapter Three: What Makes A Good Or Bad Anti-SLAPP Statute?,” The Popehat Report (July 8, 2021), https://perma.cc/THM9-L2AE. ↩︎

- In the 2023 Report Card, Colorado’s grade increased from a “B” to an “A” after a state appeals court ruling in 2022 broadly interpreted the scope of speech covered by the law. ↩︎

- The exact statutory history of New York’s anti-SLAPP law, and the nature of amendments to that law over time and how they would be evaluated under our scoring rubric, remains unclear. ↩︎

- “It’s impossible to overstate how utterly [the right to an interlocutory appeal] transforms the strategy of lawsuits aimed at speech. These days appeals usually take years. That means that if I sue over speech in a state with a strong Anti-SLAPP statute, even if I win the Anti-SLAPP motion, and then win again on appeal, I’m looking at years of delay before my case can move forward to discovery and substantive litigation. It’s a huge deterrent to censorious litigation and an incalculable benefit for defendants. Appeals, in general, are much cheaper and less disruptive than trial court litigation; it’s much easier and cheaper to file an Anti-SLAPP motion and then appeal it if you lose than it is to defend a defamation case in the trial court. This dramatically reduces the coercive effect of filing a lawsuit targeting speech.” Ken White, “What Is An Anti-SLAPP, Anyway?” ↩︎

- As described on its website, “The Uniform Law Commission (ULC, also known as the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws), established in 1892, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law…. [It is] comprised of state commissions on uniform laws from each state, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Each jurisdiction determines the method of appointment and the number of commissioners actually appointed. Most jurisdictions provide for their commission by statute…. The state uniform law commissioners come together as the Uniform Law Commission for one purpose – to study and review the law of the states to determine which areas of law should be uniform. The commissioners promote the principle of uniformity by drafting and proposing specific statutes in areas of the law where uniformity between the states is desirable.” See “About Us,” Uniform Law Commission (2023), https://perma.cc/W33C-LV2G. ↩︎

- “Public Expression Protection Act,” Uniform Law Commission (2020), https://perma.cc/L3ZH-B9N3. ↩︎

- [1] Here are minimum scores for each grade: A+, 99; A, 94; A-, 89; B+, 83; B, 78; B-, 72; C+, 67; C, 60; C-, 50; D+, 40; D, 30; D-, 10. ↩︎

- See the discussion of Missouri’s law in the Appendix. ↩︎

- See the discussion of Oklahoma’s law in the Appendix. ↩︎